|

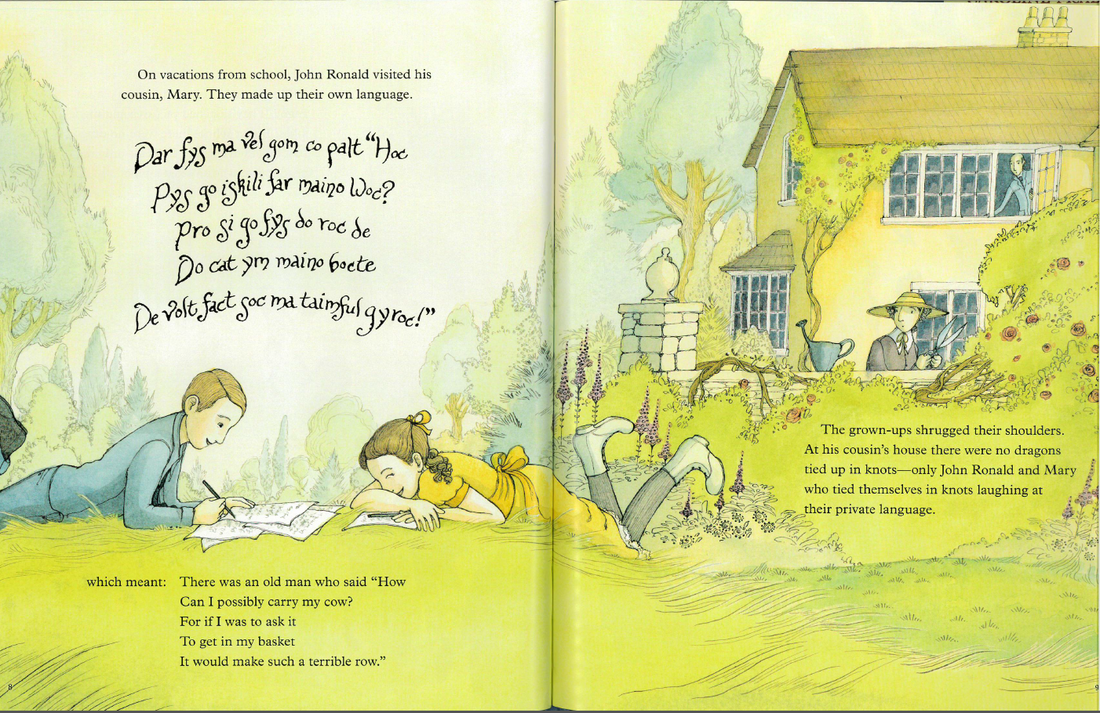

In my book, John Ronald's Dragons, I mention the origins of J. R. R. Tolkien's supremely nerdy hobby of inventing his own languages. As a child, with his cousin, Mary Incledon, he made up a language based on animal words. Later, as an adult, of course, he developed languages with full fledged grammars and histories: Quenya, and Sindarin.

In the essay "A Secret Vice" he describes this pastime as lonely and embarrassing. Although the word nerd had not yet entered the English language in 1931, he is clearly describing something all nerds experience when he explains the isolation brought on by the pursuit of a hobby not recognized by the popular or the powerful. He writes: "Most of the addicts [people addicted to inventing languages] reach their maximum of linguistic playfulness, and their interest is swamped by greater ones, they take to poetry or prose or painting, or else it is overwhelmed by mere pastimes (cricket, meccano, or suchlike footle) or crushed by cares and tasks. A few go on, but they become shy, ashamed of spending the precious commodity of time for their private pleasure, and higher developments are locked in secret places. The obviously unremunerative character of the hobby is against it--it can earn no prizes, win no competitions (as yet)--make no birthday presents for aunts (as a rule)--earn no scholarship, fellowship, or worship. It is also--like poetry--contrary to conscience, and duty; its pursuit is snatched from hours due to self-advancement, or to bread, or to employers." We can hear in this passage Tolkien's own frustration with duties that prevented him from pursuing his "secret vice" full time and sharing it publicly. He was sure that there were other people out there like him, but before the internet he had no way of meeting up with them. So he continued to toil on Quenya and Sindarin in private. But finally his hobby is having a renaissance. As Philip Seargeant points out in "Why J. R. R. Tolkien's Tradition of Creating Fantasy Languages Has Prevailed" conlangs are now popular, even cool. J. R. R. Tolkien was just ahead of his time, as his shy manifesto, "A Secret Vice" suggests. So fly your word nerd flag high and proud.

19 Comments

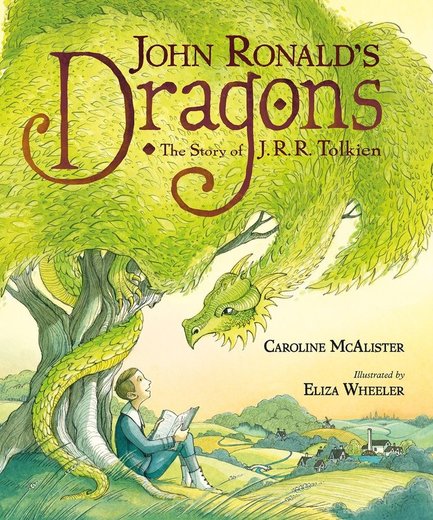

This week I got a surprise package in the mail. It was two beautiful, shiny copies of John Ronald's Dragons wrapped in a blue ribbon. They have that new book smell of fresh paper and ink. The title is embossed, and I love touching it, but what I love most of all is the cover illustration with the green tree that is also a green dragon whose head is turned towards the young John Ronald. He stares up at the dragon with wonder and delight. Eliza Wheeler has done an incredible job capturing my central idea that Tolkien's childhood desire for dragons inspired his fantasy writing as an adult. When I tell people that I write children's books, inevitably one of the first things they ask is who is your illustrator or how did you find your illustrator as though the illustrator were someone who worked for me.

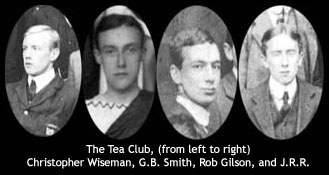

But that is not how picture books are created. I write a manuscript. Then I hold my breath and cross my fingers and if I am very lucky an editor at a publishing house will like it enough to buy it. Then we do some further editing and polishing, and the editor begins to search for an illustrator. I just have to trust that the editor has the experience and contacts and knowledge to find someone who will be able to match my words with illustrations. When Roaring Brook editor Kate Jacobs sent me a link to Eliza Wheeler's website , I was impressed by the whimsical nature of what I saw, the beautiful palettes, the sense of movement. I am not an art expert and I had not heard of Eliza before, but I liked what I saw and I trusted Kate. (Eliza just won a prestigious Sendak fellowship award. As it turns out, she is a very big deal.) Eliza sent Kate preliminary sketches for the book. Kate then shared them with me, and I was supposed to tell Kate any suggestions I had. The editor thus stands as a buffer in between the egos of the artist and the writer, a very sensible system. I remember that Kate and I had a discussion about whether Tolkien's aunt, who burned his mother's letters in the fireplace, was too witchlike. I liked that Eliza had made her appear rather like the witch in Hansel and Gretel. I thought Tolkien would appreciate that his own story had become mixed up with what he calls the soup of story in "On Fairy-Stories. " I am still a fairly new and inexperienced writer and this is my first non-fiction picture book. What I did not know was how much research Eliza would do. She travelled to Oxford and Birmingham visiting and taking pictures of the school Tolkien attended, the Oratorio where he was an altar boy, and the colleges where he worked. Eliza also read through the biographies and letters of Tolkien. She included red poppies in the world War One scene because Tolkien mentioned the poppies in his correspondence. I was especially happy with her illustration of the trenches because his war experiences were very important in shaping his imagination. All of Eliza's research means that the illustrations have incredible depth; they are not just flat representations of what is in the text. They have a life, a vibrancy of their own. They are also historically accurate. They reflect her imagination and research as well as my imagination and research, and the result is, I think, fabulous. Buy the book and let me know what you think. It will be on the bookshelves March 21. You can also pre-order on Amazon. Before Tolkien was a member of the Inklings, he was a member of the TCBS. TCBS stood for Tea Club and Barrovian Society, so named because the members had surreptitious tea parties in the school library and also drank tea together at the Barrows Store. The core members of the club were four young men who had attended King Edward's School in Birmingham together, Robert Gilson, the son of the school's headmaster, Christopher Wiseman, J. R. R. Tolkien, and G.B Smith. The young men all wrote poetry, painted, and drew. They were intellectually ambitious. As a club, they hoped to spur each other on to great accomplishments. However, their youthful ambitions were tragically upended by World War 1. In the summer of 1916, exactly one hundred years ago, all four of them had shipped out to France. They spent their days marching through mud, dodging bullets and shrapnel, and crawling through trenches filled with vermin and lice. Robert Gilson was the first to die at the Somme on July first, 1916. After receiving the news, Tolkien wrote in a letter to the remaining members of the club, dated August 12, 1916 :

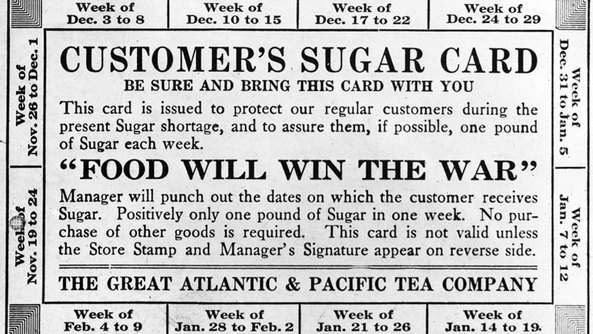

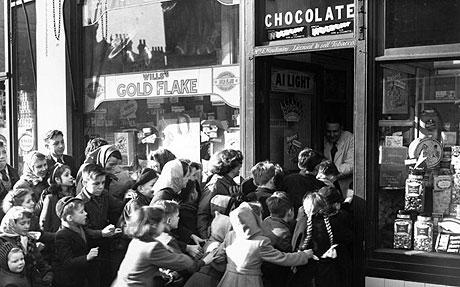

"So far my chief impression is that something has gone crack. I feel just the same to both of you--nearer if anything and very much in need of you--I am hungry and lonely of course--but I don't feel a member of a little complete body now. I honestly feel that the TCBS has ended . . . . Still I feel a mere individual at present--with intense feelings more than ideas of powerlessness"(Letters 10). G.B. Smith was wounded by a shell on November 29 and died of his wounds on December 3. Throughout the fall of 1916 Tolkien fought in the trenches, seeing notable action at the battle of Thiepval. He served as a signalman for the Lancashire Fusiliers sending out signals of troop movements, calls for more grenades, etc. On October 25 he visited the medical officer, complaining of a fever. He had contacted trench fever, which was caused by bites from the lice. He was sent home. Since the fever allowed him to escape from the front, it almost certainly saved his life. Already an orphan, Tolkien lost two of his closest companions that summer. The club they had created with so much youthful energy and hope, was no more. Tolkien only saw Christopher Wiseman a few times over the course of the rest of his life. Perhaps it was too sorrowful for the two of them to meet without the others. If there is something elegaic about the male friendships in The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings, that sadness is the result of the summer and fall of 1916. Tolkien's old school, King Edward's has a gallery of photos on the great war as well as a movie about Tolkien's experiences at the front made by students at the school. There is also a film about Robert Gilson. I also recommend Joseph Leconte's excellent article published this June in the New York Times about how Tolkien found Mordor in 1916 during the deadly summer of the Somme. In The Lion, The Witch and the Wardrobe Edmund tells the white witch where she can find his brothers and sisters while cramming his mouth full of Turkish Delight. C. S. Lewis builds up the desirability of this treat by first describing the beautiful package in which it arrives. "The Queen let another drop fall from her bottle onto the snow, and instantly there appeared a round box, tied with green silk ribbon, which, when opened, turned out to contain several pounds of the best Turkish Delight. Each piece was sweet and light to the very center and Edmund had never tasted anything more delicious." Of course, everything always tastes better when it is beautifully presented. Also, as Cara Strickland informs us, Turkish Delight was an Edwardian Christmas treat. C. S. Lewis's own childhood memories would have included opening boxes of Turkish Delight under the Christmas tree. The beautifully wrapped box evokes not just gustatory delight, but the whole experience of Christmas. The sensory appeal of Turkish delight and the moral error of Edward's gluttony would have been intensified for Lewis's readers in the early 1950's by the experience of war time rationing. I was astounded also by this other image of women rushing a chocolate shop in 1953 when rationing ended. It puts in perspective not just Edward's desire for Turkish delight, but also Roald Dahl's chiding of spoiled post war children in Charlie and the Chocolate Factory. When I teach The Chronicles of Narnia, I buy a box of Turkish Delight at our local Middle Eastern Restaurant and food store, The Nazareth Bread Company. Students are always a little mystified by what all the fuss is about when they taste the dessert. To the modern American palate, it is not terribly sweet and has a strangely plastic, unnatural texture.

A friend of mind posted this wonderful article about Hobbit food on face-book: http://oakden.co.uk/tea-in-the-hobbit/ The amazingly gifted illustrator of John Ronald's Dragons, Eliza Wheeler, has a Hobbit party every year that she makes Hobbit food for. Perhaps this true love for all things Hobbit explains why she seems to have read my mind in composing the pictures for the book.

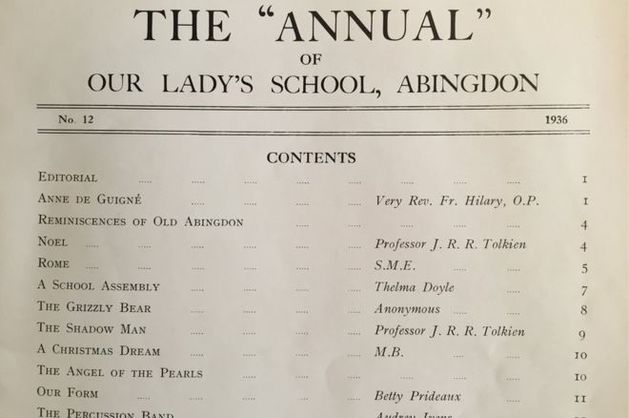

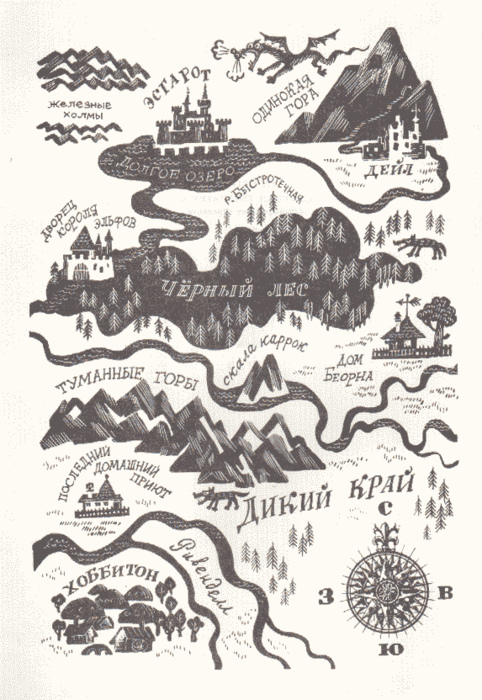

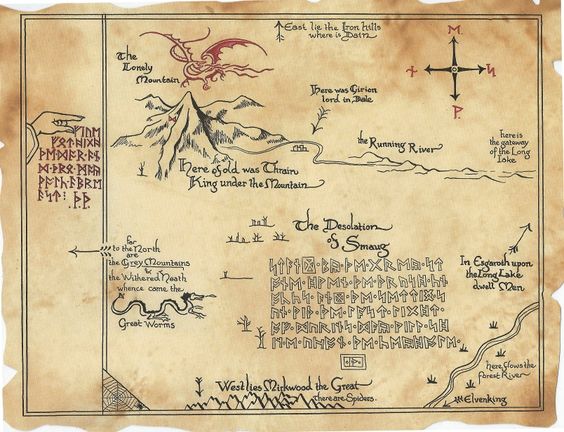

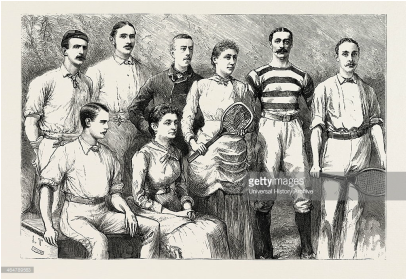

My favorite thing in this article is the explanation of the distinction between high and low tea. I will definitely use this article next time I take students to Oxford and will perhaps give extra points for participation in both a high and a low tea. I'm sorry that the recipes are all in UK measurements. They look quite old fashioned and complicated, just the sort of thing to make a huge mess in the kitchen, which i secretly like doing. I have not yet tried any of them out, but when I do I will write a post about it and include pictures of my creations.I may try some of them out on my next group of Oxford students. I stole the photo below from food.com. It is a photo of Mrs. Beeton's Seed Cake. Mine, when I make it, will be much less artful.  Exciting Tolkien news today. Two lost poems by Tolkien have been found. They were originally published in the obscure annual magazine of an Oxfordshire Catholic high school in 1936—an odd place for an Oxford Don to publish his work. However, Tolkien was not a professional poet, but an Anglo-Saxon scholar. His poetry, old fashioned and out of step with the high modernism of Eliot and Pound, would not have been picked up by the top literary journals. But clearly Tolkien valued it enough and believed in it enough that he wanted to see it published even in an obscure place. Also, the poem “Noel,” about the Virgin Mary, is deeply Catholic. What better place to share it than with a Catholic religious community dedicated to Mary. I like “Noel” very much. The first line: “Grim was the world and grey last night” gives the poem an alliterative Anglo-saxon flare. The description of the wintery world of the first two stanzas has much of The Wanderer and the Sea-farer in it. If the poem looks backward with its wistful romantic style to a Catholic medieval world, it also looks forward to the eucatastrophe. Tolkien was not just a man with his head turned to the past. He was always interested in uniting past and present and thereby redeeming the present. I have printed "Noel" below and here are the Guardian article and the BBC article about the poems’ discovery. NOEL Grim was the world and grey last night: The moon and stars were fled, The hall was dark without song or light, The fires were fallen dead. The wind in the trees was like to the sea, And over the mountains' teeth It whistled bitter-cold and free, As a sword leapt from its sheath. The lord of snows upreared his head; His mantle long and pale Upon the bitter blast was spread And hung o'er hill and dale. The world was blind, the boughs were bent, All ways and paths were wild: Then the veil of cloud apart was rent, And here was born a Child. The ancient dome of heaven sheer Was pricked with distant light; A star came shining white and clear Alone above the night. In the dale of dark in that hour of birth One voice on a sudden sang: Then all the bells in Heaven and Earth Together at midnight rang. Mary sang in this world below: They heard her song arise O'er mist and over mountain snow To the walls of Paradise, And the tongue of many bells was stirred in Heaven's towers to ring When the voice of mortal maid was heard, That was mother of Heaven's King. Glad is the world and fair this night With stars about its head, And the hall is filled with laughter and light, And fires are burning red. The bells of Paradise now ring With bells of Christendom, And Gloria, Gloria we will sing That God on earth is come.  It just arrived in the mail. My own copy of The Art of the Lord of the Rings by Wayne G. Hammond and Christina Scull. Their earlier book, J. R. R. Tolkien: Artist and Illustrator, was invaluable to me as I was doing my research for John Ronald’s Dragons. The book itself is beautiful: square shaped to match the square pieces of graph paper on which Tolkien sketched many of his preliminary maps. And this book is full of maps, from rudimentary squiggles on the back of discarded index cards to elaborate three color topographical masterpieces. It is also full of script. For those of you contemplating a tattoo with the ring inscription, you can choose from a whole variety of drafts photographed in this book. As a Tolkien lover, I am interested in maps and script and what they have to do with each other. And as a children’s writer I am interested in how learning to read maps is an exercise in literacy. In Maphead Ken Jennings points out that “a good map isn’t just a useful representation of a place; it’s also a beautiful system in and of itself” (7). As someone who studied linguistic systems, Tolkien would naturally be drawn to mapping. When the narrator of The Hobbit says of Bilbo, “ He loved maps, and in his hall there hung a large one of the Country Round with all his favourite walks marked on it in red ink,” we can intuit that Tolkien was also speaking of himself. Cartophilia was yet another way in which Tolkien was a hobbit. Maps are at once concrete and abstract. They represent an idea of place and space, but the representation is in symbols that we must learn to interpret: triangles for mountains, squiggly lines for rivers, etc. etc.. Ken Jennings notes the attraction he felt for maps as a child and suggests “that many people’s hunger for maps (mappetite?) peaks in childhood.” A map at the beginning of a children’s book is a promise. It promises adventure, travel, discovery, the unknown. As Nicholas Tam points out in his excellent blog, they enhance the reader's immersive experience of reading.  A great deal has been written by academics about maps as cultural artifacts. And several bloggers and critics have noted the charming Russian version of Thror’s map in the Russian translation of The Hobbit as proof of the cultural specificity of maps. Tolkien hated it when translators of his works attempted to translate place names, and I suspect that he might have reacted to the slavicisation of his map at the beginning of The Hobbit as he reacted to the Dutch translation of place names in his works. In a letter to his publisher, he complained: “The toponymy of The Shire . . . is a ‘parody’ of that of rural England, in much the same sense as are its inhabitants: they go together and are meant to. . . . I would not wish, in a book starting from an imaginary mirror of Holland, to meet Hedge, Duke’sbush, Eaglehome, or Applethorn even if these were ‘translations’ of ‘sGravenHage, Hertogenbosch, Arnhem, or Apeldoorn! These translations are not English, they are just homeless.” Many people have written more eloquently about Tolkien’s maps than I. Here is a wonderful blog about fantasy maps with a detailed discussion of Thror's map. And here is a review of The Art of the Lord of the Rings from Wired Magazine. Today is the finals of the Australian Open, and tomorrow is the Iowa Caucus, both of which bring us naturally to Lewis Carroll. Yes, the man who created Wonderland was interested in both lawn tennis and in elections. He wanted to make them both fairer, more logical, more mathematically perfect. Carroll was compelled to write about the rules of lawn tennis tournaments after talking to an acquaintance who was upset after he lost in the first round and then saw a player much weaker than himself make his way into the finals. Of course, they didn’t have seeding back then. Draws were composed randomly, so the best and second best players could very easily meet in the first round. Carroll offered his solution in his pamphlet named, “Lawn Tennis Tournaments, The True Method of Assigning Prizes with a Proof of the Fallacy of the Present Method.” Importantly, he did not propose a seeding system like we use today. That would have been too simple. Instead, he created a complex tournament structure in which players could not be eliminated in the first round. Loosers kept playing until they had three superiors, three people who had beaten them or beaten someone who had beaten them. I am a bit of a tennis fanatic and play in a USTA League and I am now dying to set up a tournament using Carroll’s scheme. What should we call it? The mad tea party tournament? Or perhaps the completely fair and logical Reverend Charles Lutwidge Dodgson Tournament. Here is an article by Rachel Bachman from the Wall Street Journal about Carroll’s tournament format: http://www.wsj.com/articles/SB10001424052702304636404577297821444746352. I am much indebted to it for explaining his complex system. Carroll’s obsession with fairness also took him into the arena of elections. He wrote three pamphlets about elections. He was upset not just by unfairness in national elections, but also by unfairness in Oxford University elections. Imagine a university with an unfair system! Here is an article by Glenn C. Joy entitled “Ballots in the Belfry: Lewis Carroll and Voting Fairness”: file:///C:/Users/Owner/Downloads/NMWT_2002_Joy_BallotsInTheBelfryLewisCar.pdf .  Wonderland is full of games that are immensely unfair and illogical. Take the croquet game, which is played on an uneven turf and uses live creatures for balls and mallets. Carroll explains through Alice’s point of view: Alice thought she had never seen such a curious croquet-ground in her life: it was all ridges and furrows: the croquet balls were live hedgehogs, and the mallets live flamingoes, and the soldiers had to double themselves up and stand on their hands and feet, to make the arches. The live creatures make it a game of random chance rather than skill. They also make it wonderfully loopy and fun and imaginative. Could Carroll be mocking here a Victorian game that is a bit staid and stuffy? He wants rules that are fair and that work, but he also loves defying rules and logic. Alice says to the Cheshire Cat: “I don’t think they play at all fairly,” Alice began, in rather a complaining tone, “and they all quarrel so dreadfully one ca’n’t hear oneself speak—and they don’t seem to have any rules in particular: at least, if there are, nobody attends to them—and you’ve no idea how confusing it is all the things being alive: for instance, there’s the arch I’ve got to go through next walking about at the other end of the ground—and I should have croqueted the Queen’s hedgehog just now, only it ran away when it saw mine coming.” On the one hand, I hear in Alice’s petulance Lewis Carroll’s frustration with a world that does not work logically. He was, after all, a logician. On the other hand, how much more fun and wondrous is a game with live creatures than a game with plain wooden sticks and wire wickets? Just look at this picture of a real Victorian croquet game. It is not at all inspiring. I am indebted to Alice Medinger for reminding me of the Caucus Race and its connection to American politics in her beautifully illustrated blog post: https://medinger.wordpress.com/2016/01/26/lewis-carrolls-caucus-race/.

The caucus race is another illogical and unfair game. Again, the course is uneven and the rules are unclear. First it [the Dodo] marked out a race-course, in a sort of circle, (“the exact shape doesn’t matter,” it said,) and then all the party were placed along the course, here and there. There was no “One, two three, and away!” but they began running when they liked, so that it was not easy to know when the race was over. What on earth would Carroll have made of this year’s Iowa caucuses? In Alice in Wonderland, when everyone asks the Dodo who has won the caucus race, he says: “Everybody has won, and all must have prizes.” What if the election in Iowa doesn’t eliminate any candidates? What if everyone wins and keeps running around in “a sort of circle” endlessly? It feels as though this has already happened. Carroll was eerily prescient. Thanks to my daughter Abby for finding this wonderful Mentalfloss article with recordings of Tolkien reading from The Lord of the Rings.

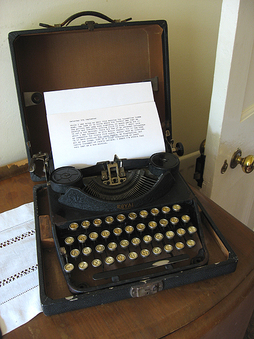

http://mentalfloss.com/article/73909/listen-jrr-tolkien-read-and-sing-excerpts-lord-rings The fantasy writer, Diana Wynne Jones reported famously that Tolkien's lectures were inaudible, disorganized and mumbling. He suffered a laceration of his tongue while playing rugby at King Edward's School in Birmingham, one possible explanation for the mumbling. But in these recordings his speech is lovely. He rolls his r's. He projects. He is rhythmic. He chuckles at his own jokes. It is sheer magic to hear this voice.  I am always fascinated by the physical ways that people write, by the technologies they choose or don't choose. There is a Royal typewriter at the Kilns, but C. S. Lewis never used it. In fact, he never learned to type at all. He wrote long hand in school exercise books and used an ink-pen that he had to dip in an inkwell--very messy and impractical. Apparently Mr.s Moore hated the inkwell, which he sometimes knocked over and spilled. But stopping to dip the pen in the well was an important part of his writing rhythm. It forced him to pause. In those pauses, he gathered his thoughts, he read the words out loud to himself (and he could hear the words without the interference of tip tapping) and he did recursive editing in his head. Lewis wrote quickly and usually did not take things through a second draft. The ink pen was the only thing that slowed him down. In this way he was the opposite of Tolkien, who composed very slowly, wrote multiple drafts and typed and retyped them himself often to save money. Overwhelmed with the expenses of having a family, he couldn't afford to pay a typist. Of course, Jack's typist was very conveniently his brother Warnie. As an army Officer in Charge of Supplies Warnie would have had to spend many hours in front of a typewriter, filling out forms. He apparently typed very fast although he only used two fingers. And he believed wholeheartedly in his brother and his genius. Typing Jack's papers and correspondence gave him a purpose and was much more fulfilling than typing forms for the army. In addition to never learning to type, Jack never learned how to drive. The scenes of him diving in Shadowlands are pure Hollywood. He loved to walk. He often walked all the way home to Headington from Oxford. He famously became convinced of the truth of Christianity while walking with Tolkien and Hugo Dyson. He took long walking tours with his brother and with other Inklings. On these tours the men would discuss philosophy, religion, and literary criticism. Somehow the movement of their legs, the rhythm of their steps would facilitate the movement of their thoughts. Thought and language are inseparable and rhythm is important to both. The Royal typewriter captures beautifully the relationship between the two brothers. It captures their different personalities; Warnie's more technological bent, his love of machines, boats, train and Jack's literary leanings, his absorption in pre-modern worlds and fantasy. It illustrates their dependence on one another. Warnie needed Jack to keep him away from alcohol, loneliness, depression. Jack needed Warnie to ground him, to remind him of his childhood and to help him type his manuscripts and organize his immense correspondence. NOTES FOR WRITERS AND TEACHERS OF WRITING

First of all, artifacts like the Royal typewriter are great sources of inspiration, great triggers for one's own writing. The Royal typewriter gave me the idea to write a book about C.S. Lewis using the angle of his friendship with his brother. Second of all, it is always good to be aware of the technologies that help us or hurt us while we are writing. What did we use when we first learned to write? What is habitual for us? Does our writing come out differently if we write a draft long hand before transitioning to the typewriter? And when we choose a technology, how much do sound, rhythm and timing matter? Computers give us the ability to compose at lighting speed, but is that always good? Do we loose the sound or sense of what we are writing if we go too fast? |

Caroline McAlisterCaroline is an avid reader, children's writer, and teacher. She lives in North Carolina with her husband and dog. Check out her bio for more! Archives

February 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed