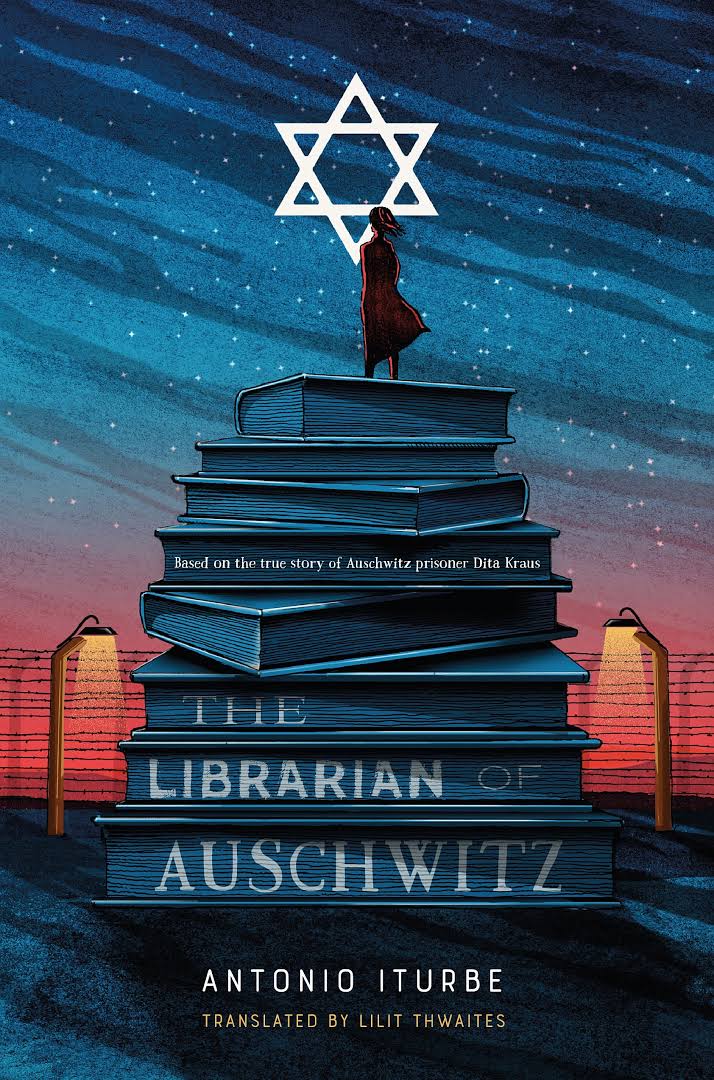

I have found blogging discouraging. I write and post and then nobody responds. However, I recently received an intriguing message from the other side of the world (Australia) to one of my earliest posts. I had read a New York Times Op-Ed by Alberto Manguel about a secret library at Auschwitz. I was haunted by the idea of children in a concentration camp seeking comfort in books. Here is the blog I posted. It turns out I was not the only person haunted by Alberto Manguel's mention of a secret library at Auschwitz. In 2011 a Spanish journalist, Antonio Iturbe, read Manguel's book, The Library at Night, and using his considerable journalistic skills, he went in search of information. He found the actual librarian, the older girl, in charge of the eight threadbare books. Her name was Dita Kraus and she was then 80 years old and living in Israel. He wrote a novel in Spanish based on her story. The English translation, elegantly done by Lilit Thwaites, was just published to great acclaim this October by Henry Holt. Lilit's husband came across my blog post and contacted me. I promised to read and review The Librarian of Auschwitz, which I stayed up finishing last night, with a box of kleenex at my side. The Librarian of Auschwitz is the perfect follow up to Anne Frank for the young adult and adult reader. It details the horrors of the camps, the inhumanity of genocide, and the amazing spirit and light of those individuals whose names and stories we must never forget. Here in the US, where fascists chanting "blood and soil" march with tiki torches through the lovely town of Charlottesville, we especially need to be reminded. But, The Librarian of Auschwitz is not just about the holocaust. It is also a story about the magic of books. Iturbe describes eloquently the power of books to transport readers to other places and times. What could be more important than to escape metaphorically for an hour from the horrors of a concentration camp? As Iturbe explains, for Dita this magical power inhered not just in novels, but even in H. G. Wells's A Short History of the World: A Short History of the World is the library book borrowed most frequently because it's the closest thing to a regular schoolbook. And there's no question that when she buries herself in its pages, she feels as if she were back at her school in Prague, and that if she were to raise her head, she'd see in front of her the blackboard and her teacher's hands covered in chalk. (114) Here Wells' book returns her to the comfort of her life before it was interrupted by war. But it also carries her far, far away. That's why she prefers to return to the pages about ancient Egypt, which immerse her in the world of pharoahs with mysterious names and allow her to board the boats that navigate the Nile. H. G. Wells is right. There really is a time machine--books". (116) Dita is in charge of not just books on paper, but also living books, the stories narrated by gifted tellers. One of the most moving scenes in the novel is when a fellow inmate tells Dita the story of The Count of Monte Cristo. She is drawn to the figure of Edmond Dantes. She also wonders if, were she successful [in escaping], she'd dedicate her life to taking revenge on all the SS guards and officers, and if she'd do it in the same methodical, implacable, and yes, even merciless, manner as the Count of Monte Cristo. Of course she'd be delighted if they suffered the same pain they inflicted on so many innocent people. But nevertheless, she can't avoid feeling some sadness at the thought that she liked the happy and confident Edmond Dantes of the beginning of the story more than the calculating, hate-filled man he became. (278) Here books give her a way to explore the ethics of revenge and to sort through the immensely complicated emotions of her experience.

It was through the magic of books, specifically Alberto Manguel's book, The Library at Night, that Iturbe came across Dita's story. I am thankful to him. I am thankful to Iturbe for writing the novel that has brought the story to life, and I am thankful to Lilit Thwaites for making the novel available to English speaking audiences. I am thankful to Lilit's husband to reaching out to me. Books have ripple effects. One cannot anticipate how and where these ripples will expand. It is my hope that the waves from The Librarian of Auschwitz will reach far and wide for a long time to come.

7 Comments

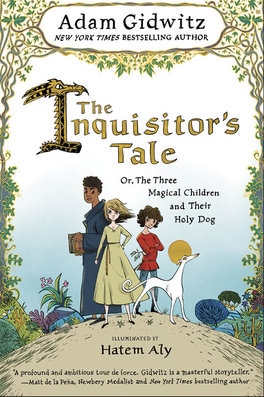

First I want to thank Eliza Wheeler's amazing husband who had the computer skills to put together this trailer for John Ronald's Dragons. The way he makes the figures in the background move is called parallaxing. As someone who struggles daily with simple classroom management software (moodle an canvas ugh!) I am forever impressed by and grateful to those who can combine technical and creative skills with grace. Second, I want to point out that last Saturday, March 25th, was Tolkien reading day. Our Carolinas SCBWI leader, Teresa Fannin, sent me a beautiful article explaining the significance of the date. Apparently dates in Tolkien's books are just as carefully chosen as the names of his characters. I celebrated Tolkien reading day by reading John Ronald's Dragons at Scuppernong's Bookstore, a warm, quirky community bookstore in downtown Greensboro. Third, I want to review a book I read over my spring break, Adam Gidwitz's middle grade novel The InQuisitor's Tale.  The Inquisitor's Tale by Adam Gidwitz is amazing! This is the book I wish I had written. It is the book I wish I could go back and read to my kids using my special time turner travel kit. It is the book I wish the college kids I teach had grown up reading because it would make them wise, thoughtful, and literate about that strange country, the past, more specifically the past of the middle ages. Adam Gidwitz's three main characters are two boys and a girl as in the Harry Potter formula, but he builds on this formula by adding a dog and by making one child black, one child Jewish, and one child a peasant, thus taking on the topics of class, race, and religion. Gidwitz builds on actual Saints' legends, which are great and gory stories, and mixes them up with the modern superhero trope. And what are saints but superheros with magical powers? The mash up makes the past new and the present old. Again following a classic kid lit formula the three children are relieved of parental comfort and authority early in the novel. In picaresque fashion they wander the French countryside and have adventures with silly knights, a farting dragon, a close minded queen, and a fat angel. But along with the fart jokes, Gidwitdz takes on deep questions: the origins of mistrust and conflict between Christians and Jews, the construction of racial difference, the banning and burning of books and the biggest question--if God is good, why does he allow terrible suffering. Also, the book is beautiful to behold. The illustrator, Hatem Aly, has decorated the margins with charming illuminations and doodles that are like the text, historically informed but also modern. I now want to read the book a second time (I had to read it really fast the first time to find out what happens), and dawdle and peruse the pictures and their relationship to the text. I also love that this is a book about mutual understanding between different religions and the author is Jewish and the illustrator is Muslim. What could be more perfect? And for adults who read the book to their children (and why wouldn't you?) you must read the elegant author's note which explains how much of the story is based on actual medieval legends and lore. In the process of reporting on food books for the class I am taking on non-fiction picture books taught by the awesome Candice Ransom, I found one book that is good enough to eat--A Fine Dessert: Four Centuries, Four Families, One Delicious Treat written by Emily Jenkins and illustrated by Sophie Blackall. The book depicts four different families making blackberry fool in four different centuries, 1710, 1810, 1910 and 2010. The concept is simple and straightforward and at the same time sophisticated and elegant. First the book demonstrates how cooking technology has changed over time. The first family beats cream with a bundle of sticks, the next with a wire whisk, the next with a manual egg beater, and the last with an electric mixer. Emily Jenkins tells us exactly how long it takes to make whipped cream with each implement. More importantly, however, the author and illustrator depict changes in social structure and gender roles. In 1710 a girl and her mother make the dessert. In 1810 in Charleston an enslaved girl and her mother make the dessert and lick the bowl in secret. In 2010 a boy and his father make the dessert together, and a mixed race family joins them for dinner. This apparently simple book describes beautifully how change happens over time in domestic spaces that are not usually thought of as places where history happens.

The writing is full of sensuous details. For example: “Their hands turned purple with the juice. The thorns of the berry bushes pricked the fabric of their long skirts.” Sophie Blackall’s illustrations remind me of 19th century primitive portraits and needlework. The twirling blackberry vines frame vignettes of cooking, and the end pages are actually painted a luscious dark purple using actual blackberry juice. |

Caroline McAlisterCaroline is an avid reader, children's writer, and teacher. She lives in North Carolina with her husband and dog. Check out her bio for more! Archives

February 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed