|

Today is the finals of the Australian Open, and tomorrow is the Iowa Caucus, both of which bring us naturally to Lewis Carroll. Yes, the man who created Wonderland was interested in both lawn tennis and in elections. He wanted to make them both fairer, more logical, more mathematically perfect. Carroll was compelled to write about the rules of lawn tennis tournaments after talking to an acquaintance who was upset after he lost in the first round and then saw a player much weaker than himself make his way into the finals. Of course, they didn’t have seeding back then. Draws were composed randomly, so the best and second best players could very easily meet in the first round. Carroll offered his solution in his pamphlet named, “Lawn Tennis Tournaments, The True Method of Assigning Prizes with a Proof of the Fallacy of the Present Method.” Importantly, he did not propose a seeding system like we use today. That would have been too simple. Instead, he created a complex tournament structure in which players could not be eliminated in the first round. Loosers kept playing until they had three superiors, three people who had beaten them or beaten someone who had beaten them. I am a bit of a tennis fanatic and play in a USTA League and I am now dying to set up a tournament using Carroll’s scheme. What should we call it? The mad tea party tournament? Or perhaps the completely fair and logical Reverend Charles Lutwidge Dodgson Tournament. Here is an article by Rachel Bachman from the Wall Street Journal about Carroll’s tournament format: http://www.wsj.com/articles/SB10001424052702304636404577297821444746352. I am much indebted to it for explaining his complex system. Carroll’s obsession with fairness also took him into the arena of elections. He wrote three pamphlets about elections. He was upset not just by unfairness in national elections, but also by unfairness in Oxford University elections. Imagine a university with an unfair system! Here is an article by Glenn C. Joy entitled “Ballots in the Belfry: Lewis Carroll and Voting Fairness”: file:///C:/Users/Owner/Downloads/NMWT_2002_Joy_BallotsInTheBelfryLewisCar.pdf .  Wonderland is full of games that are immensely unfair and illogical. Take the croquet game, which is played on an uneven turf and uses live creatures for balls and mallets. Carroll explains through Alice’s point of view: Alice thought she had never seen such a curious croquet-ground in her life: it was all ridges and furrows: the croquet balls were live hedgehogs, and the mallets live flamingoes, and the soldiers had to double themselves up and stand on their hands and feet, to make the arches. The live creatures make it a game of random chance rather than skill. They also make it wonderfully loopy and fun and imaginative. Could Carroll be mocking here a Victorian game that is a bit staid and stuffy? He wants rules that are fair and that work, but he also loves defying rules and logic. Alice says to the Cheshire Cat: “I don’t think they play at all fairly,” Alice began, in rather a complaining tone, “and they all quarrel so dreadfully one ca’n’t hear oneself speak—and they don’t seem to have any rules in particular: at least, if there are, nobody attends to them—and you’ve no idea how confusing it is all the things being alive: for instance, there’s the arch I’ve got to go through next walking about at the other end of the ground—and I should have croqueted the Queen’s hedgehog just now, only it ran away when it saw mine coming.” On the one hand, I hear in Alice’s petulance Lewis Carroll’s frustration with a world that does not work logically. He was, after all, a logician. On the other hand, how much more fun and wondrous is a game with live creatures than a game with plain wooden sticks and wire wickets? Just look at this picture of a real Victorian croquet game. It is not at all inspiring. I am indebted to Alice Medinger for reminding me of the Caucus Race and its connection to American politics in her beautifully illustrated blog post: https://medinger.wordpress.com/2016/01/26/lewis-carrolls-caucus-race/.

The caucus race is another illogical and unfair game. Again, the course is uneven and the rules are unclear. First it [the Dodo] marked out a race-course, in a sort of circle, (“the exact shape doesn’t matter,” it said,) and then all the party were placed along the course, here and there. There was no “One, two three, and away!” but they began running when they liked, so that it was not easy to know when the race was over. What on earth would Carroll have made of this year’s Iowa caucuses? In Alice in Wonderland, when everyone asks the Dodo who has won the caucus race, he says: “Everybody has won, and all must have prizes.” What if the election in Iowa doesn’t eliminate any candidates? What if everyone wins and keeps running around in “a sort of circle” endlessly? It feels as though this has already happened. Carroll was eerily prescient.

21 Comments

Thanks to my daughter Abby for finding this wonderful Mentalfloss article with recordings of Tolkien reading from The Lord of the Rings.

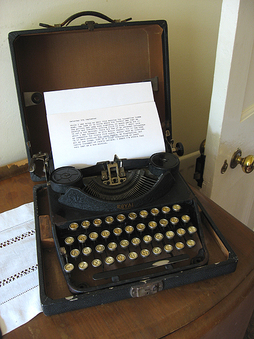

http://mentalfloss.com/article/73909/listen-jrr-tolkien-read-and-sing-excerpts-lord-rings The fantasy writer, Diana Wynne Jones reported famously that Tolkien's lectures were inaudible, disorganized and mumbling. He suffered a laceration of his tongue while playing rugby at King Edward's School in Birmingham, one possible explanation for the mumbling. But in these recordings his speech is lovely. He rolls his r's. He projects. He is rhythmic. He chuckles at his own jokes. It is sheer magic to hear this voice.  I am always fascinated by the physical ways that people write, by the technologies they choose or don't choose. There is a Royal typewriter at the Kilns, but C. S. Lewis never used it. In fact, he never learned to type at all. He wrote long hand in school exercise books and used an ink-pen that he had to dip in an inkwell--very messy and impractical. Apparently Mr.s Moore hated the inkwell, which he sometimes knocked over and spilled. But stopping to dip the pen in the well was an important part of his writing rhythm. It forced him to pause. In those pauses, he gathered his thoughts, he read the words out loud to himself (and he could hear the words without the interference of tip tapping) and he did recursive editing in his head. Lewis wrote quickly and usually did not take things through a second draft. The ink pen was the only thing that slowed him down. In this way he was the opposite of Tolkien, who composed very slowly, wrote multiple drafts and typed and retyped them himself often to save money. Overwhelmed with the expenses of having a family, he couldn't afford to pay a typist. Of course, Jack's typist was very conveniently his brother Warnie. As an army Officer in Charge of Supplies Warnie would have had to spend many hours in front of a typewriter, filling out forms. He apparently typed very fast although he only used two fingers. And he believed wholeheartedly in his brother and his genius. Typing Jack's papers and correspondence gave him a purpose and was much more fulfilling than typing forms for the army. In addition to never learning to type, Jack never learned how to drive. The scenes of him diving in Shadowlands are pure Hollywood. He loved to walk. He often walked all the way home to Headington from Oxford. He famously became convinced of the truth of Christianity while walking with Tolkien and Hugo Dyson. He took long walking tours with his brother and with other Inklings. On these tours the men would discuss philosophy, religion, and literary criticism. Somehow the movement of their legs, the rhythm of their steps would facilitate the movement of their thoughts. Thought and language are inseparable and rhythm is important to both. The Royal typewriter captures beautifully the relationship between the two brothers. It captures their different personalities; Warnie's more technological bent, his love of machines, boats, train and Jack's literary leanings, his absorption in pre-modern worlds and fantasy. It illustrates their dependence on one another. Warnie needed Jack to keep him away from alcohol, loneliness, depression. Jack needed Warnie to ground him, to remind him of his childhood and to help him type his manuscripts and organize his immense correspondence. NOTES FOR WRITERS AND TEACHERS OF WRITING

First of all, artifacts like the Royal typewriter are great sources of inspiration, great triggers for one's own writing. The Royal typewriter gave me the idea to write a book about C.S. Lewis using the angle of his friendship with his brother. Second of all, it is always good to be aware of the technologies that help us or hurt us while we are writing. What did we use when we first learned to write? What is habitual for us? Does our writing come out differently if we write a draft long hand before transitioning to the typewriter? And when we choose a technology, how much do sound, rhythm and timing matter? Computers give us the ability to compose at lighting speed, but is that always good? Do we loose the sound or sense of what we are writing if we go too fast?  My editor asked me to do some edits on "Warnie and Jack's Wardrobe," a book about the friendship between C. S. Lewis and his brother Warren Hamilton Lewis. I found myself looking through the letters Jack wrote to Warnie when Warnie was called up for active duty at the beginning of World War 2 in 1939. At this time Warnie would have been 44 years old and Jack 41. One detail that intrigued me was Jack's description of preparing for blackouts to evade German bombs. "The main trouble of life at present is the blacking out which is done (as you may imagine) with a most complicated Arthur Rackham system of odd rags--quite effectively, but at the cost of much labour"(168). When I visited The Kilns with my Guilford students, the tour guides have pointed out the thick blackout curtains in Jack's study. I was also struck by Jack's descriptions of the refugee children. He writes to his brother, "I have said that the children are 'nice,' and so they are. But modern children are poor creatures. They keep on coming to Maureen and asking, 'What shall we do now?' She tells them to play tennis, or mend their stockings, or write home; and when that is done, they come and ask again. Shade of our childhood . . . !" Of course, he and Warnie knew how to occupy themselves building imaginary worlds. I can see in this passage how the presence of children in the house made him think of Little Lea and Boxen and got him started thinking about a whole world behind the old wardrobe. |

Caroline McAlisterCaroline is an avid reader, children's writer, and teacher. She lives in North Carolina with her husband and dog. Check out her bio for more! Archives

February 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed