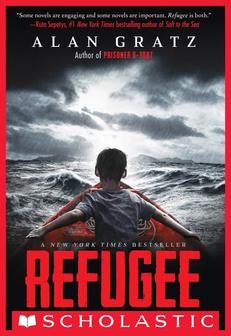

I work at Guilford College, a historically Quaker institution and my colleague, Diya Abdo has begun an initiative, Every Campus a Refuge, to house refugees on college campuses, using student and faculty volunteers to help settle and work with the families. I have done a little work with ECAR, but after reading Alan Gratz’s book Refugee, I will definitely try to do more. There are many reasons kids (and their parents) should read Refugee. First of all there is the sheer pleasure of getting lost in a well-constructed page turner. Every chapter ends with a cliff hanger. The interwoven narratives increase the tension. Alan Gratz leaves readers on the edge of a precipice and then they have to speed through the next two chapters before finding out whether one of the three protagonists lives or dies. The cultural and historical details are interesting, authentic, educational, and introduced without clumsy information dumps. (My daughter is studying abroad in Cuba this semester and I was tickled to see how many details of Cuban life that she has relayed to us were included in the book). But the main reason kids should read Alan Gratz’s book is that refugee crises are a children’s issue. As the pictures in the news of children covered in dust or drowned on the beaches reveal, children are there, front and center. (Gratz mentions in the back matter that the image of Omram Daqneesh sitting in an ambulance inspired the character of Mahmoud's younger brother, Waleed.) These pictures display children as passive victims, but in Gratz’s book, the children have agency; they make choices; they take initiative. The child reader, identifying with them, is empowered and grows through their experiences. Take Josef, the boy from Nazi Germany, who flees to Cuba. With his father traumatized by the violence and inhumanity of a concentration camp, he must step up and become the man of the family. Isabel, the Cuban fleeing to America, trades her beloved trumpet for gas for their boat. Mahmoud, fleeing Syria for Germany, decides that it is more important to be visible than invisible and initiates a mass exodus from a detention center. In each narrative the roles of child and adult shift and transform as the children, jolted out of their ordinary lives, must perform feats of amazing bravery and strength. I am always interested in the backstory of books. Gratz tells in an interview how he and his family were on vacation in the Florida Keys and came upon a raft on the beach, a crude water craft clearly built of scrap materials to carry refugees from Cuba. The experience reminded him of his own privilege and ignited his curiosity. Drawing on the emotions and ideas provoked by this experience, he made boats and water a central motif in Refugee. Josef and his family sail on the unlucky MS St. Louis. The boat that Isabel travels in is cobbled together from fragments of this and that with an ironic poster of Castro on the bottom. Mahmoud makes a terrifying journey on a rubber dinghy across the Mediterranean in the dark. For all three families bodies of water, the space in between, provide escape and salvation, but also bring unmentionable terrors. In conclusion, the intertwined narratives make clear the perennial, ongoing nature of refugee crises. By profiling one family fleeing from Germany and another fleeing to Germany, one family fleeing from Cuba and another fleeing to Cuba, Gratz cleverly reveals how history repeats itself, but always with a twist. How does one become a refugee? Simply by being born in the wrong place at the wrong time. Gratz has said that he likes to remind children that unless they are Native Americans, someone in their family came here at some point as a refugee. Refugee teaches and encourages not just empathy, but activism. For my own part, I will now try to up my volunteer hours with ECAR.

11 Comments

|

Caroline McAlisterCaroline is an avid reader, children's writer, and teacher. She lives in North Carolina with her husband and dog. Check out her bio for more! Archives

February 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed