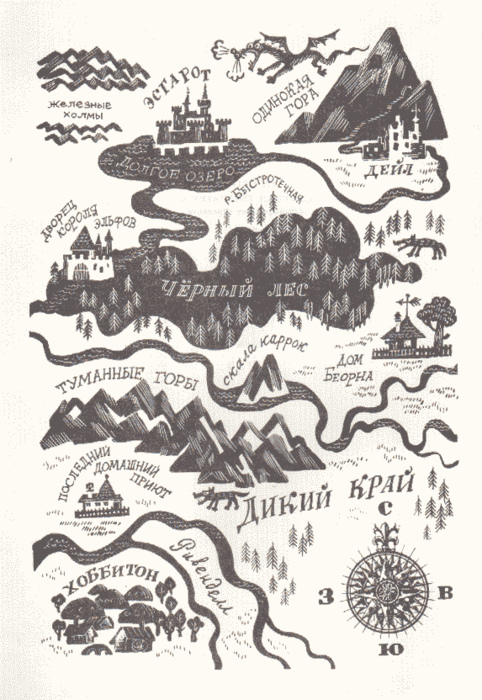

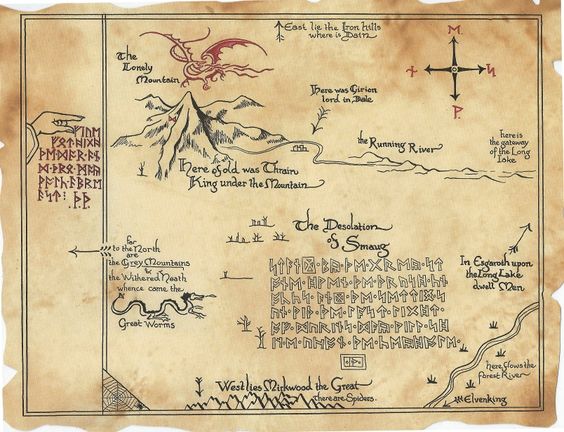

It just arrived in the mail. My own copy of The Art of the Lord of the Rings by Wayne G. Hammond and Christina Scull. Their earlier book, J. R. R. Tolkien: Artist and Illustrator, was invaluable to me as I was doing my research for John Ronald’s Dragons. The book itself is beautiful: square shaped to match the square pieces of graph paper on which Tolkien sketched many of his preliminary maps. And this book is full of maps, from rudimentary squiggles on the back of discarded index cards to elaborate three color topographical masterpieces. It is also full of script. For those of you contemplating a tattoo with the ring inscription, you can choose from a whole variety of drafts photographed in this book. As a Tolkien lover, I am interested in maps and script and what they have to do with each other. And as a children’s writer I am interested in how learning to read maps is an exercise in literacy. In Maphead Ken Jennings points out that “a good map isn’t just a useful representation of a place; it’s also a beautiful system in and of itself” (7). As someone who studied linguistic systems, Tolkien would naturally be drawn to mapping. When the narrator of The Hobbit says of Bilbo, “ He loved maps, and in his hall there hung a large one of the Country Round with all his favourite walks marked on it in red ink,” we can intuit that Tolkien was also speaking of himself. Cartophilia was yet another way in which Tolkien was a hobbit. Maps are at once concrete and abstract. They represent an idea of place and space, but the representation is in symbols that we must learn to interpret: triangles for mountains, squiggly lines for rivers, etc. etc.. Ken Jennings notes the attraction he felt for maps as a child and suggests “that many people’s hunger for maps (mappetite?) peaks in childhood.” A map at the beginning of a children’s book is a promise. It promises adventure, travel, discovery, the unknown. As Nicholas Tam points out in his excellent blog, they enhance the reader's immersive experience of reading.  A great deal has been written by academics about maps as cultural artifacts. And several bloggers and critics have noted the charming Russian version of Thror’s map in the Russian translation of The Hobbit as proof of the cultural specificity of maps. Tolkien hated it when translators of his works attempted to translate place names, and I suspect that he might have reacted to the slavicisation of his map at the beginning of The Hobbit as he reacted to the Dutch translation of place names in his works. In a letter to his publisher, he complained: “The toponymy of The Shire . . . is a ‘parody’ of that of rural England, in much the same sense as are its inhabitants: they go together and are meant to. . . . I would not wish, in a book starting from an imaginary mirror of Holland, to meet Hedge, Duke’sbush, Eaglehome, or Applethorn even if these were ‘translations’ of ‘sGravenHage, Hertogenbosch, Arnhem, or Apeldoorn! These translations are not English, they are just homeless.” Many people have written more eloquently about Tolkien’s maps than I. Here is a wonderful blog about fantasy maps with a detailed discussion of Thror's map. And here is a review of The Art of the Lord of the Rings from Wired Magazine.

6 Comments

|

Caroline McAlisterCaroline is an avid reader, children's writer, and teacher. She lives in North Carolina with her husband and dog. Check out her bio for more! Archives

February 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed