My editor asked me to do some edits on "Warnie and Jack's Wardrobe," a book about the friendship between C. S. Lewis and his brother Warren Hamilton Lewis. I found myself looking through the letters Jack wrote to Warnie when Warnie was called up for active duty at the beginning of World War 2 in 1939. At this time Warnie would have been 44 years old and Jack 41. One detail that intrigued me was Jack's description of preparing for blackouts to evade German bombs. "The main trouble of life at present is the blacking out which is done (as you may imagine) with a most complicated Arthur Rackham system of odd rags--quite effectively, but at the cost of much labour"(168). When I visited The Kilns with my Guilford students, the tour guides have pointed out the thick blackout curtains in Jack's study. I was also struck by Jack's descriptions of the refugee children. He writes to his brother, "I have said that the children are 'nice,' and so they are. But modern children are poor creatures. They keep on coming to Maureen and asking, 'What shall we do now?' She tells them to play tennis, or mend their stockings, or write home; and when that is done, they come and ask again. Shade of our childhood . . . !" Of course, he and Warnie knew how to occupy themselves building imaginary worlds. I can see in this passage how the presence of children in the house made him think of Little Lea and Boxen and got him started thinking about a whole world behind the old wardrobe.

9 Comments

In “Reinventing the Library,” an Op-Ed in the New York Times dated October 23, 2015 Alberto Manguel describes a collection of children’s books at Auschwitz-Birkenau: Libraries come in countless shapes and sizes. They can be like the Library of Congress or as modest as that of the children’s concentration camp in Auschwitz-Birkenau, where the older girls were in charge of eight volumes that had to be hidden every night so that the Nazi guards wouldn’t confiscate them.  I don’t know where to start to research this story. I wonder what the eight volumes were. What books brought comfort to children in the midst of hopelessness and horror? Did the books have pictures? Did the older girls read them to the little girls at night? Did a book possibly save a child’s life, give a single child the strength to endure until the liberation? Did a book remind a child of normalcy, of family, of love? Does anyone out there know where Manguel got this story from, where I could read more about it? Where did the children hide the books? The article also resonated with me as we had to decide what to do with my father’s books as we moved my parents into a rest home. My father grew up in a small town in Arkansas that did not have a library. He never had books as a child. As an adult he collected them feverishly, coffee table art books, cookbooks with beautiful photographs, gardening books, books about opera, and dictionaries and reference books. We couldn’t explain to him why the dictionaries and reference books were no longer valuable. His collection for him was symbolic, symbolic of the life he had built as a professor, as a lover of art, and as a family man who passed his love of books on to his daughters and grandchildren. Books provide comfort to the young and the old and become a part of one’s identity. Postscript: I ordered Alberto Manguel’s book, The Library at Night. I discovered that the secret library was in B lock 31, an extension of Auschwitz set up for propaganda purposes that housed five hundred children in a “family camp” to demonstrate that the Germans were not killing deported children. Books contained in the library were, H.G. Wells’s A Short History of the World, a Russian school textbook, and an analytical geometry text. Manguel also mentions the importance of stories that children memorized and told each other at night. Alberto Manguel discusses reading as an act of resistance to oppression. I dream about the children at Auschwitz reading to each other at night. I dream about my father trying to hold on to his library as he loses the ability to hear, the interact, to remember his past. http://www.nytimes.com/2015/10/12/opinion/the-importance-of-recreational-math.html?_r=0 It’s funny for me to be writing a blog post in response to an article about recreational math. I am after all the most mathematically challenged person in the universe. My children realized by about fourth grade that they had already surpassed me. When students ask what they need to make on a test to get an A in my class, I tell them they will have to do that math themselves. But enough about my math challenges. I was surprised to see in the article the name Martin Gardner and to discover that he was famous in the math world for creating elaborate puzzles. I, of course, know Martin Gardner as the editor of the annotated Alice in Wonderland. And it makes perfect sense that as a mathematician, Martin Gardner would be interested in Lewis Carroll. Lewis Carroll taught mathematics and logic at Oxford.

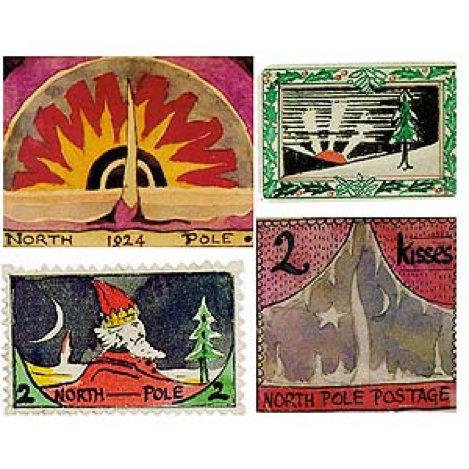

But the more important connection between Gardner and Carroll is their love of puzzles and play, their belief that learning should be fun. Perhaps if I had played more mathematical games, I would have less trouble now adding up my students’ grades. And I certainly hope, as the article suggests, that recreational mathematics will find a place in the Common Core. http://www.theguardian.com/books/2015/oct/23/jrr-tolkien-middle-earth-annotated-map-blackwells-lord-of-the-rings I was thrilled and intrigued to read about this new discovery of Tolkien “ephemera” as Blackwells calls it. The map reveals many of the reasons I love Tolkien. First of all, it shows how much his imagination was visual as well as textual and linguistic. He was a happy man with a sketch pad and a set of ink pens; his artwork helped feed his writing and vice versa. Consider the careful details that went into just the imaginary postage stamps on his Father Christmas letters. Just the lettering itself on the stamps is beautiful. Tolkien understood that text could be art and art could be text.

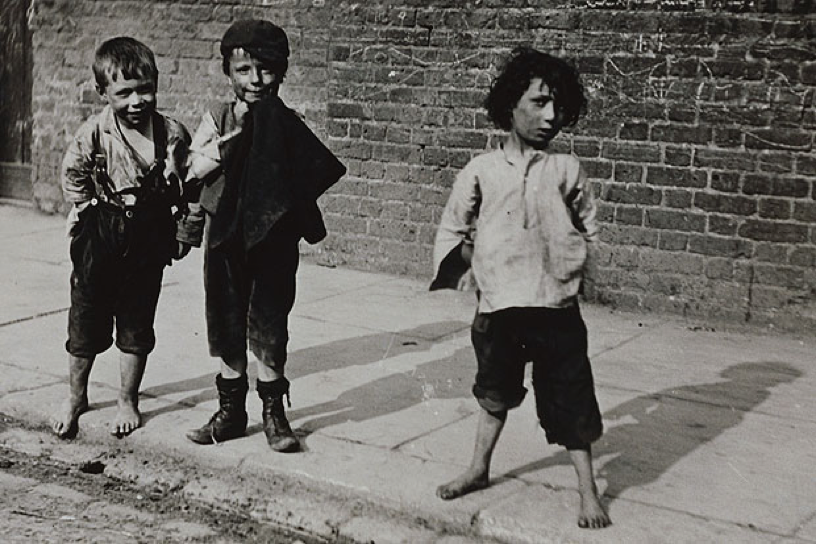

The discovery also reveals his love of maps, which Bilbo Baggins shared with him. “He loved maps, and in his hall there hung a large one of the country round with all his favorite walks marked on it in red ink.” Maps were integral to Tolkien’s fantasy worlds, to his plots, to his writing process. As writers we could all learn from him to do more mapping. And most importantly of all, the detailed annotations reveal his scholarly, curmudgeonly insistence on perfection. They reveal his desire to control how his work was printed and transmitted down to the smallest minutiae. Hooray for Tolkien! What a great find! In the early hours of the morning of May 22, 1867 Charles Dodgson worked feverishly on a one-hundred line poem that opposed the Vice-Chancellor of Oxford’s Decree of April 29 calling for the conversion of a park in North Oxford into a cricket pitch. The poem he wrote is a parody of Oliver Goldsmith’s “The Deserted Village” (1770). It should not surprise us that Dodgson framed his protest in this parodic form, but why did he care, what did he have against the sport of cricket, and what can we learn from this controversy about his conception of childhood? First of all, he laments the artificial levelling of the naturally rolling grounds of the park. Adown thy glades, all sacrificed to cricket, Thy hollow-sounding bat now guards the wicket; Sunk are thy mounds in shapeless level all, Lest aught impede the swiftly rolling ball; And trembling, shrinking from the fatal blow, Far, far away thy hapless children go. The destruction of this natural space has displaced its natural inhabitants, children. In the romantic tradition, Dodgson identifies children here as a part of nature and as vulnerable to Victorian “progress.” But the children he describes are not privileged drawing room children like Alice Liddell, daughter of the Dean of Christ Church College, but “urchins.” He deplores the loss of the “charms” belonging to, The never-failing brawl, the busy mill Where tiny urchins vied in fistic skill-- (Two phrases only have that dusky race Caught from the learned influence of the place; Phrases in their simplicity sublime, “Scramble a copper!” “Please, Sir, what’s the time?”) These round thy walks their cheerful influence shed; These were they charms—but all these charms are fled. A man of his age and an essentialist, Dodgson conflates race and class when he refers to the unwashed, coal smudged children as “that dusky race.” But more importantly he idealizes the freedom of the brawling, fighting “urchins” whom he considers much closer to nature than the drawing room child. This idealization helps to explain why he photographed Alice barefoot dressed as a beggar. Supervised by her governess, Miss Prickett, and shuffled between lessons and fittings by her ambitious mother, Alice could only pretend to be a child of nature.

Of course it is deeply problematic to idealize and prettify childhood poverty, but Dodgson was on to something in opposing the overly structured lives of middle and upper class Victorian children. In a letter to May Forshall, one of his child friends, he wrote: “Do you ever play at games? Or is your idea of life “breakfast, lessons, dinner, lessons, tea, lessons, bed, lessons, breakfast, lessons,” and so on? It is a very neat plan of life and almost as interesting as being a sewing machine or a coffee grinder.” Just the word coffee grinder evokes images of Dickens’ Mr. Gradgrind stuffing facts down little childrens’ throats and destroying their imaginations. When he asks Miss Forshall if she plays at “games,” Dodgson does not mean exclusive, organized sports like cricket, which he associates with wealth and privilege. Ill fares the place, to luxury a prey, Where wealth accumulates, and minds decay; Athletic sports may flourish or may fade, Fashion may make them, even as it has made; But the broad Parks, the city’s joy and pride, When once destroyed can never be supplied! Rather he means the kind of imaginative games that children invent on their own, games without “pavilions” and “scorers’ tents,” games without winners and losers, games without complicated and absurd rules. Dodgson was obsessed with childhood and children because they represented for him freedom from the oppressive constraints of Victorian life. They represented freedom from finicky indoor spaces, freedom from ticking wristwatches, freedom from attention to manners and dress, and finally freedom from the burdens of his academic work. In the process of reporting on food books for the class I am taking on non-fiction picture books taught by the awesome Candice Ransom, I found one book that is good enough to eat--A Fine Dessert: Four Centuries, Four Families, One Delicious Treat written by Emily Jenkins and illustrated by Sophie Blackall. The book depicts four different families making blackberry fool in four different centuries, 1710, 1810, 1910 and 2010. The concept is simple and straightforward and at the same time sophisticated and elegant. First the book demonstrates how cooking technology has changed over time. The first family beats cream with a bundle of sticks, the next with a wire whisk, the next with a manual egg beater, and the last with an electric mixer. Emily Jenkins tells us exactly how long it takes to make whipped cream with each implement. More importantly, however, the author and illustrator depict changes in social structure and gender roles. In 1710 a girl and her mother make the dessert. In 1810 in Charleston an enslaved girl and her mother make the dessert and lick the bowl in secret. In 2010 a boy and his father make the dessert together, and a mixed race family joins them for dinner. This apparently simple book describes beautifully how change happens over time in domestic spaces that are not usually thought of as places where history happens.

The writing is full of sensuous details. For example: “Their hands turned purple with the juice. The thorns of the berry bushes pricked the fabric of their long skirts.” Sophie Blackall’s illustrations remind me of 19th century primitive portraits and needlework. The twirling blackberry vines frame vignettes of cooking, and the end pages are actually painted a luscious dark purple using actual blackberry juice. |

Caroline McAlisterCaroline is an avid reader, children's writer, and teacher. She lives in North Carolina with her husband and dog. Check out her bio for more! Archives

February 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed