|

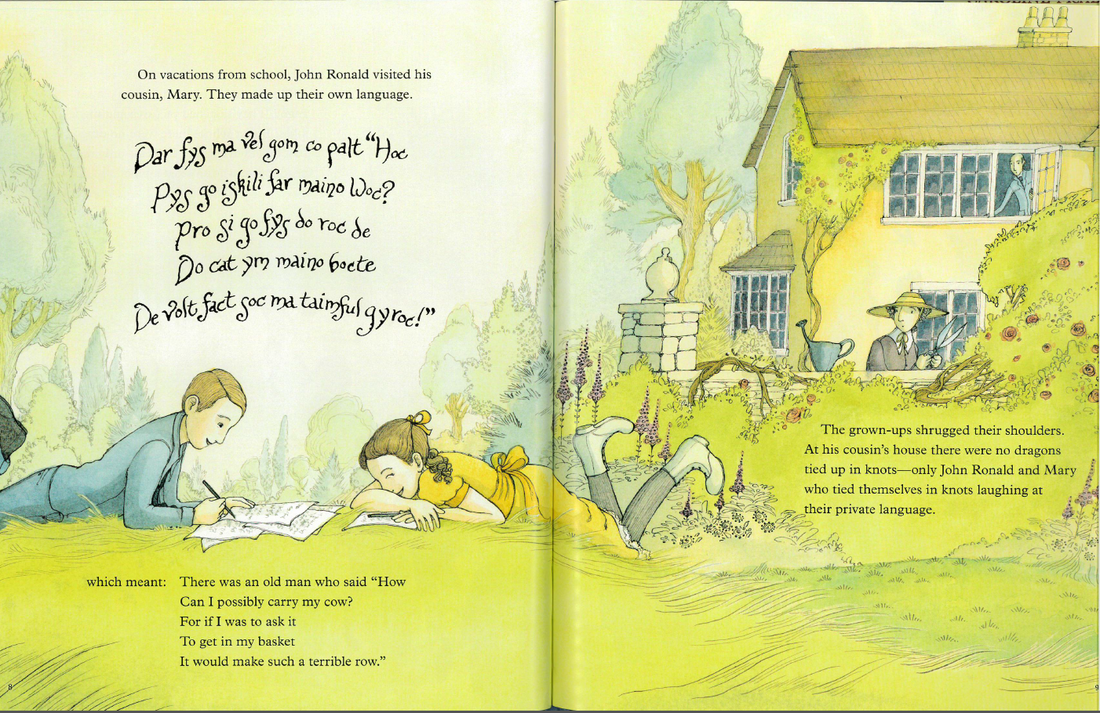

In my book, John Ronald's Dragons, I mention the origins of J. R. R. Tolkien's supremely nerdy hobby of inventing his own languages. As a child, with his cousin, Mary Incledon, he made up a language based on animal words. Later, as an adult, of course, he developed languages with full fledged grammars and histories: Quenya, and Sindarin.

In the essay "A Secret Vice" he describes this pastime as lonely and embarrassing. Although the word nerd had not yet entered the English language in 1931, he is clearly describing something all nerds experience when he explains the isolation brought on by the pursuit of a hobby not recognized by the popular or the powerful. He writes: "Most of the addicts [people addicted to inventing languages] reach their maximum of linguistic playfulness, and their interest is swamped by greater ones, they take to poetry or prose or painting, or else it is overwhelmed by mere pastimes (cricket, meccano, or suchlike footle) or crushed by cares and tasks. A few go on, but they become shy, ashamed of spending the precious commodity of time for their private pleasure, and higher developments are locked in secret places. The obviously unremunerative character of the hobby is against it--it can earn no prizes, win no competitions (as yet)--make no birthday presents for aunts (as a rule)--earn no scholarship, fellowship, or worship. It is also--like poetry--contrary to conscience, and duty; its pursuit is snatched from hours due to self-advancement, or to bread, or to employers." We can hear in this passage Tolkien's own frustration with duties that prevented him from pursuing his "secret vice" full time and sharing it publicly. He was sure that there were other people out there like him, but before the internet he had no way of meeting up with them. So he continued to toil on Quenya and Sindarin in private. But finally his hobby is having a renaissance. As Philip Seargeant points out in "Why J. R. R. Tolkien's Tradition of Creating Fantasy Languages Has Prevailed" conlangs are now popular, even cool. J. R. R. Tolkien was just ahead of his time, as his shy manifesto, "A Secret Vice" suggests. So fly your word nerd flag high and proud.

19 Comments

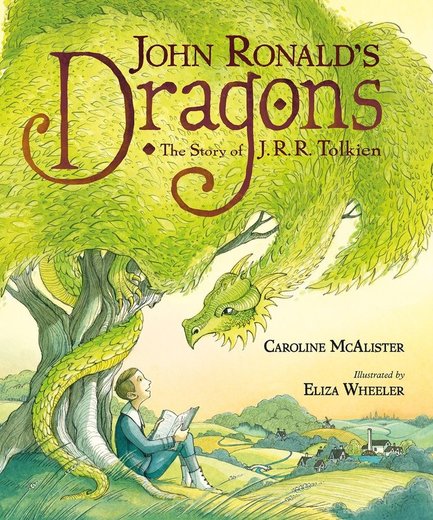

This week I got a surprise package in the mail. It was two beautiful, shiny copies of John Ronald's Dragons wrapped in a blue ribbon. They have that new book smell of fresh paper and ink. The title is embossed, and I love touching it, but what I love most of all is the cover illustration with the green tree that is also a green dragon whose head is turned towards the young John Ronald. He stares up at the dragon with wonder and delight. Eliza Wheeler has done an incredible job capturing my central idea that Tolkien's childhood desire for dragons inspired his fantasy writing as an adult. When I tell people that I write children's books, inevitably one of the first things they ask is who is your illustrator or how did you find your illustrator as though the illustrator were someone who worked for me.

But that is not how picture books are created. I write a manuscript. Then I hold my breath and cross my fingers and if I am very lucky an editor at a publishing house will like it enough to buy it. Then we do some further editing and polishing, and the editor begins to search for an illustrator. I just have to trust that the editor has the experience and contacts and knowledge to find someone who will be able to match my words with illustrations. When Roaring Brook editor Kate Jacobs sent me a link to Eliza Wheeler's website , I was impressed by the whimsical nature of what I saw, the beautiful palettes, the sense of movement. I am not an art expert and I had not heard of Eliza before, but I liked what I saw and I trusted Kate. (Eliza just won a prestigious Sendak fellowship award. As it turns out, she is a very big deal.) Eliza sent Kate preliminary sketches for the book. Kate then shared them with me, and I was supposed to tell Kate any suggestions I had. The editor thus stands as a buffer in between the egos of the artist and the writer, a very sensible system. I remember that Kate and I had a discussion about whether Tolkien's aunt, who burned his mother's letters in the fireplace, was too witchlike. I liked that Eliza had made her appear rather like the witch in Hansel and Gretel. I thought Tolkien would appreciate that his own story had become mixed up with what he calls the soup of story in "On Fairy-Stories. " I am still a fairly new and inexperienced writer and this is my first non-fiction picture book. What I did not know was how much research Eliza would do. She travelled to Oxford and Birmingham visiting and taking pictures of the school Tolkien attended, the Oratorio where he was an altar boy, and the colleges where he worked. Eliza also read through the biographies and letters of Tolkien. She included red poppies in the world War One scene because Tolkien mentioned the poppies in his correspondence. I was especially happy with her illustration of the trenches because his war experiences were very important in shaping his imagination. All of Eliza's research means that the illustrations have incredible depth; they are not just flat representations of what is in the text. They have a life, a vibrancy of their own. They are also historically accurate. They reflect her imagination and research as well as my imagination and research, and the result is, I think, fabulous. Buy the book and let me know what you think. It will be on the bookshelves March 21. You can also pre-order on Amazon. |

Caroline McAlisterCaroline is an avid reader, children's writer, and teacher. She lives in North Carolina with her husband and dog. Check out her bio for more! Archives

February 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed