Cover Reveal for A Line Can Go Anywhere: The Brilliant, Resilient Life of Artist Ruth Asawa5/9/2024

2 Comments

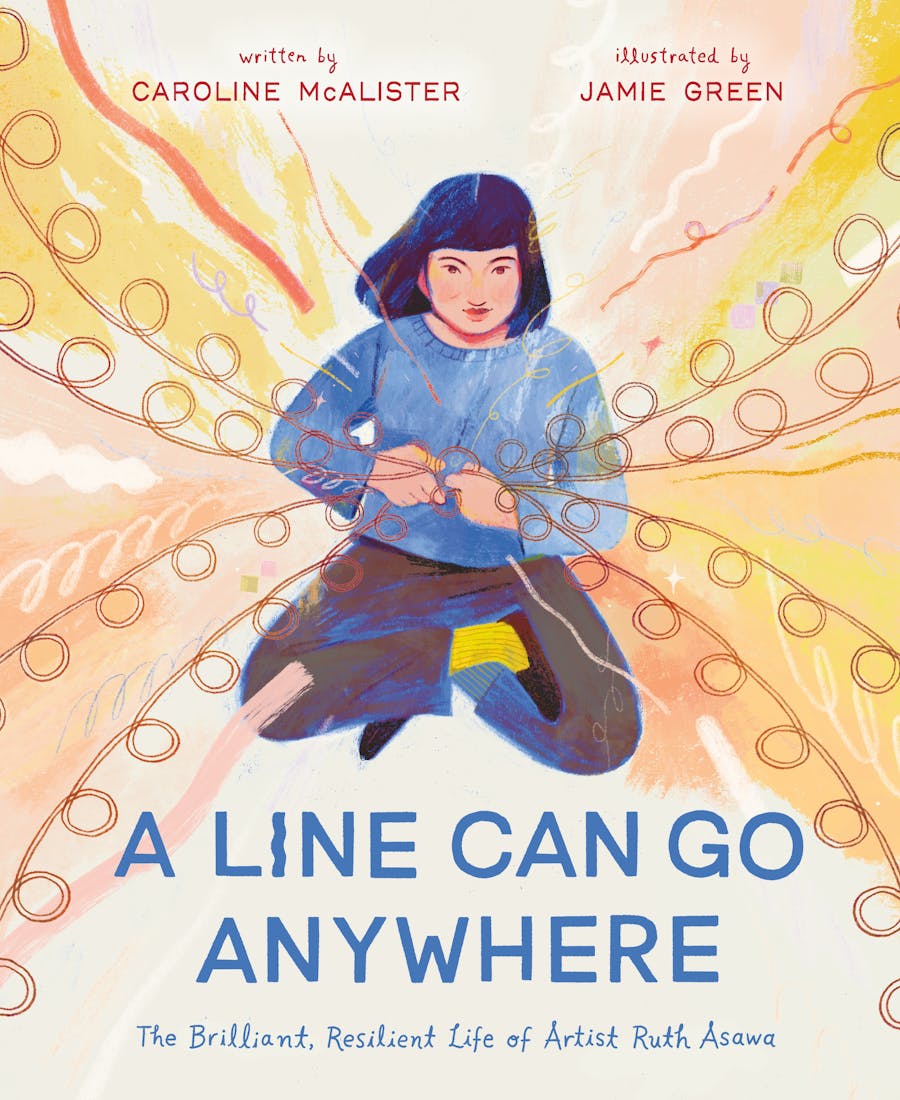

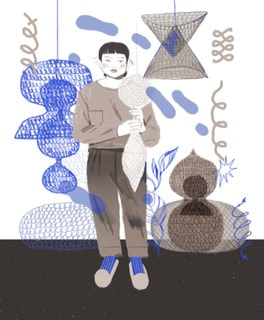

My big news is I have a new book coming out in February 2025. Here is the notice from the Rights Report. Kate Jacobs while at Roaring Brook bought world rights to Sculpting a Life: The Story of Ruth Asawa, written by Caroline McAlister (l.) and illustrated by Jamie Green (Mushroom Rain); Emily Feinberg will edit. The picture book biography traces budding artist Asawa's journey from a Japanese American Incarceration camp to the legendary Black Mountain College, and, ultimately, to the creation of her iconic woven wire sculptures. Publication is set for 2025; Jennifer Mattson at Andrea Brown Literary Agency represented the author, and Chad W. Beckerman at the CAT Agency represented Green. Since the rights report came out, we have changed the title to “A Line Can Go Anywhere:” The Brilliant, Resilient Life of Ruth Asawa.

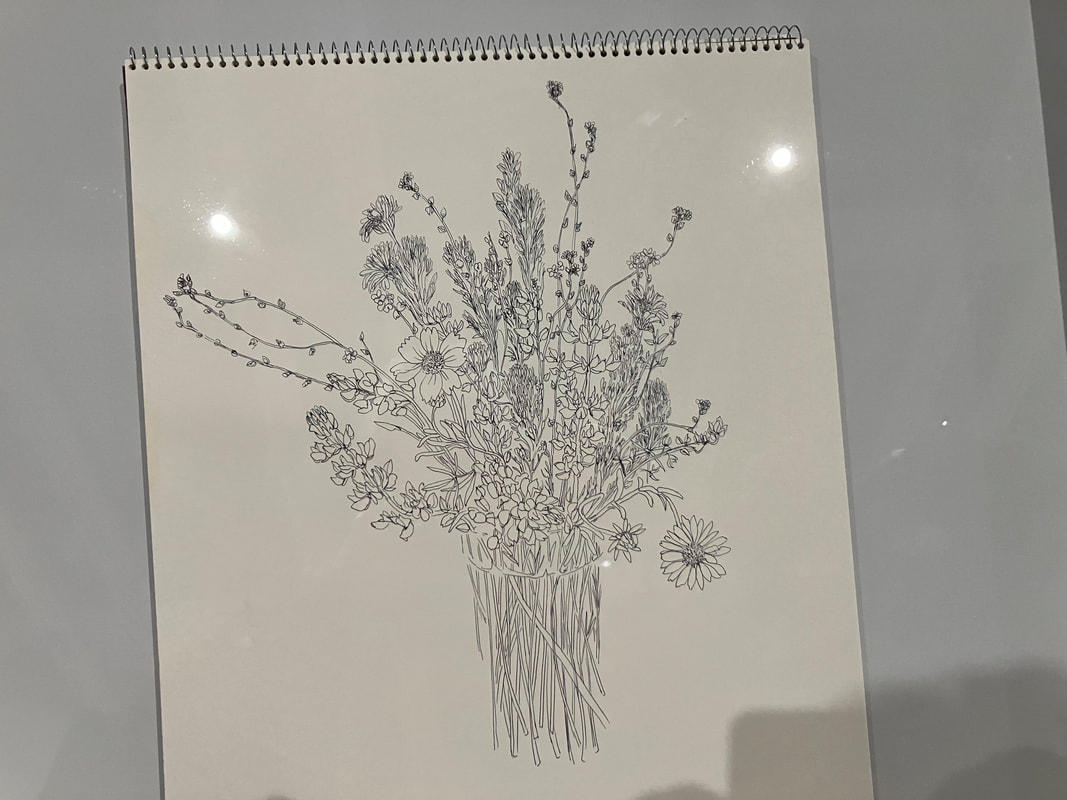

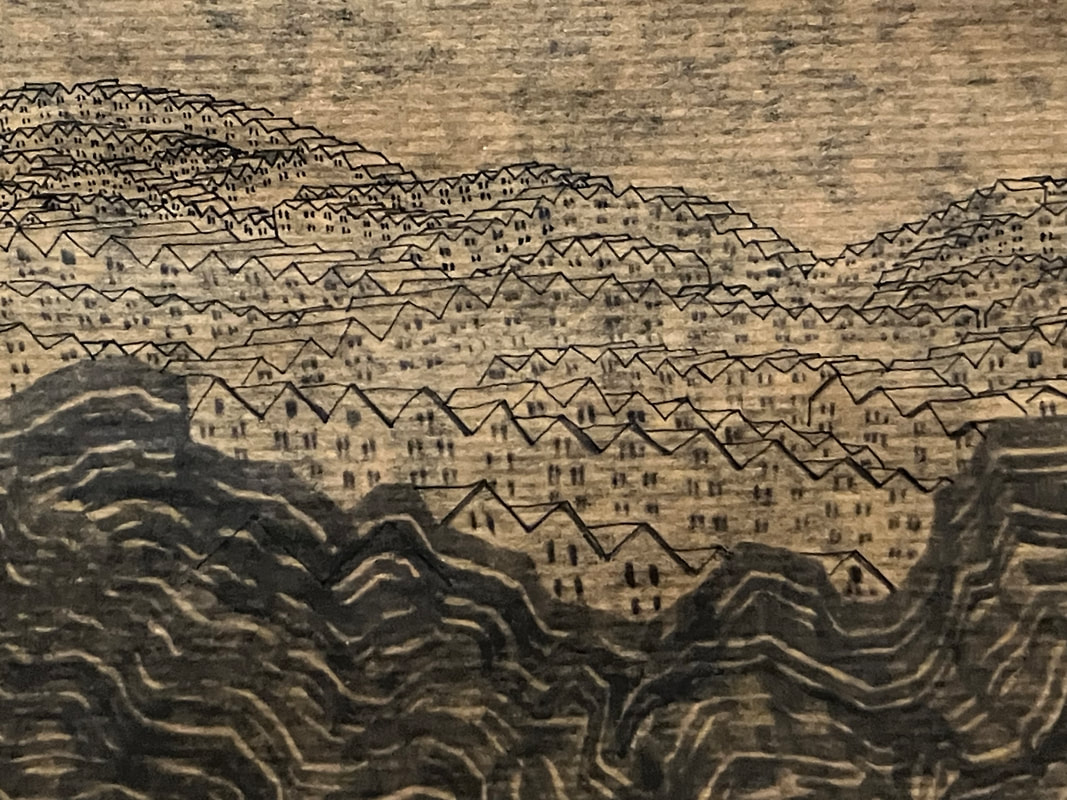

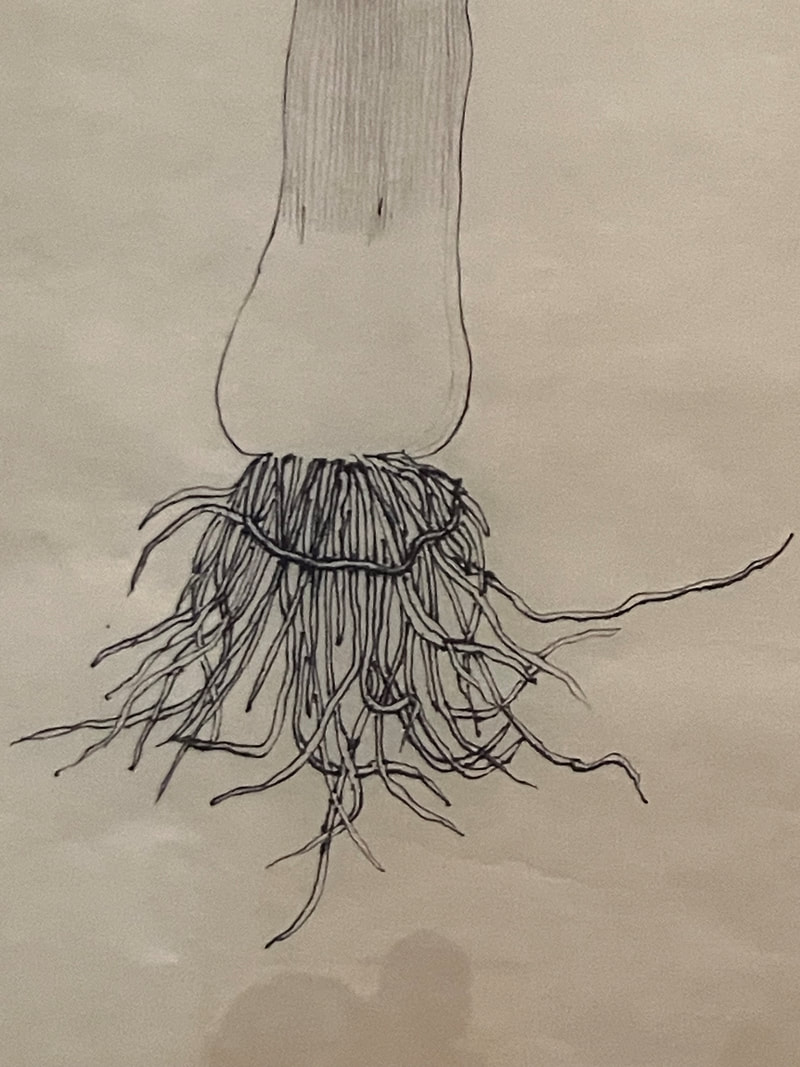

I am super jazzed about working with Jamie Green who illustrated the amazing Mushroom Rain. Check out Jamie’s work here: https://www.jamiegreenillustration.com/ Here are a couple of samples of what Jamie is planning for the book.  Finding Narnia is my second book with Macmillan; the release date is November 19. For both John Ronald's Dragons and Finding Narnia the production process feels a little mysterious from my end. Out of the blue I'll get an e-mail from editor Katherine Jacobs informing me of the release date. Then an ARC, advance release copy, will land on my doorstep. Then e-mails arrive with copies of the reviews. If a review is negative, my agent, Jennifer Mattson, will try to provide soothing words and context. But with Finding Narnia the two reviews I have received have been wonderful, so no soothing words necessary, only kudos and joy. But especially kudos and joy for the starred Kirkus review!  ★ FINDING NARNIA The Story of C. S. Lewis and His Brother Warnie Author: Caroline McAlister, Illustrator: Jessica Lanan Publisher: Roaring Brook, Pages: 48 Price (Hardcover): $19.99 Publication Date: November 19, 2019, ISBN (Hardcover): 9781626726581 A vivid portrait of inspiration and imagination focuses on teamwork and historical fact.C.S. "Jack" and Warren "Warnie" Lewis were brothers and best friends, curious dreamers and inspired playmates, but they probably never guessed that their games would help fire the imaginations of generations of children. Following the two from early childhood to later life, straightforward, energetic text paired with appealing, specific, and skillful illustrations provides background for the genesis of Lewis' ideas (Norse legend, Raj-era India, Irish shipyards, and English boarding schools all played a role). However, rather than exclusively focusing on interesting or chronological details (though both are included), McAlister looks at how Narnia was born. She finds its roots in the brothers' invented worlds, their on-again, off-again partnership, the different directions their lives took, the behavior of wartime refugee children who stayed in their home, and, of course, the presence of a magical wardrobe in their childhood. Lanan's paintings combine homey views of the family's Belfast house, pictures, maps, and diagrams of their imagined world, and luminous, magical paintings of Narnia. In a nice touch, the focus extends to the endnotes, where McAlister, as biographer, and Lanan, as illustrator, mention their own research discoveries and related artistic choices.Masterfully explains how a classic series came to be while maintaining a sense of mystery and wonder. (Picture book/biography. 4-8)  ,So I've been trying to expand my repertoire beyond the picture book biography, and to that end, I have been reading a lot of middle grade novels. My favorite at the moment is Rooftoppers by Katherine Rundell. I found out about her because she had reviewed The British Library's Harry Potter exhibition for the London Review of Books. www.lrb.co.uk/v39/n24/katherine-rundell/at-the-british-library. She grew up on Rowling's books and shares with her a genius for the tropes of classic British children's fiction: quasi-fantastical Victorian settings, orphans, and eccentric guardians. The gangs of enterprising street children are reminiscent of Charles Dickens and Eric Kastner.  Apparently Rundell was inspired to write Rooftoppers by her own adventures climbing the roofs of Oxford. (It is no accident that Philip Pullman blurbs her book.) Here is a link to an article she wrote about climbing for the London Review of Books. www.lrb.co.uk/v37/n08/katherine-rundell/diary I am interested, however, in what I can learn as an aspiring middle grade writer from Rundell. I feel my weakness is plot so I am intrigued by how other authors construct theirs. The plot of Rooftoppers is driven by the main character's, Sophie's, desire for her lost mother. Although Sophie is still an infant when she is separated from her mother, she has memories: "Sophie's skin was too pale, and it showed blotches in the cold, and her hair had never, in her memory, been without knots. Sophie did not mind, though, because in her memory of her mother she saw the same sort of hair and skin--and her mother, she felt sure, was beautiful. Her mother, she was sure, had smelled of cool air and soot, and had worn trousers with patches at the ankle" (13). I love the detail of the patches at the ankle because a small child would notice things at ankle height. But to get back to plot, everything depends on these memories of love and connection. Sophie clings fiercely and stubbornly to them, coming to think of herself as a "mother-hunter." So lesson number one is the plot must be driven by the main character's desire. In children's fiction the desire for a parent's love is powerful. Lesson number two has to do with the obstacles Rundell creates for Sophie to overcome before she can realize her desires. She faces external obstacles: a conformist child services bureaucrat, unhelpful French authorities (imagine!), and a feral gang of French street children. But she also faces internal obstacles: her fear of the water and her fear of heights. The internal and external obstacles are inextricable. She cannot overcome one without overcoming the other. So lesson number two is throw exciting challenges in front of your character that create tension, but also allow the character to grow internally and mature. Lesson number three has to do with Rundell's similes. I love the way she uses similes to describe feelings, especially feelings of joy and wonder connected to music and reading. For example, she describes how Sophie's eccentric guardian sings with perfect pitch: "Charles had no musical instruments, but he sang to her, and when Sophie was elsewhere, he sang to the birds, and to the wood lice that occasionally invaded the kitchen. His voice was pitch-perfect. It sounded like flying" (10). Then there is the first time that Sophie hears cello music: "It was so beautiful that it was difficult for her to breathe. If music can shine, Sophie thought, this music shone. It was like all the voices in all the choirs in the city rolled into a single melody. Her chest felt oddly swollen" (24). And most wonderful of all is the description of a good cello practice session. "When the music went right, it drained all the itch and fret from the world and left it glowing. When she did stretch and blink and lay her bow down hours later, Sophie would feel tougher, and braver. It was, she thought, like having eaten a meal of cream and moonlight" (26). A meal of cream and moonlight! I love that she uses synaesthesia, comparing the sound of music to the taste of food. I once went to a talk by Itzhak Pearlman and he described Beethoven as sounding like beef. Lesson number three: the writer's job is to make the reader experience what she describes, and synaesthetic similes can do that. I will obey the rule of three and stop here. If you read this post, please let me know what middle grade novels you have enjoyed and what writing tips you have gleaned from them. P. S. Here is one more link to an article about Rundell's newest book, The Explorer, which I may just have to read next.  What I most love about Philip Pullman's La Belle Sauvage is the attention to the minute details of making things by hand, for example, the locks that Mr. Taphouse builds for the priory at Godstow, the hoops in neat brackets that Lord Asriel has affixed to Malcolm's canoe, and even the food prepared by Sister Fenella: "Nothing was wasted at the priory. The little pieces of pastry Sister Fenella had left after trimming her rhubarb pies were formed into clumsy crosses or fish shapes, or rolled around a few currants, then sprinkled with sugar and baked separately" (5). I have never done woodworking or carpentry but the passages devoted to cooking really spoke to me. Malcolm helps Sister Fenella peel potatoes and prepare brussel sprouts. When she is finished she puts the leavings in the stock pot: "Sister Fenella gathered up the discarded sprout leaves and cut the stalks in half a dozen pieces and put them in a bin for stock" (18). I was so intrigued by these details I started saving scraps and made my own vegetable stock for my new year's Hoppin' John--cilantro stalks, celery leaves, onion skins, kale stems. The results were delicious. These details anchor Pullman's fantasy in the reality of the physical world. They also serve as a metaphor for his own craft of writing. How fun to think of writing like cooking--taking scraps from our own lives, from the world around us, from the books we read and admire, and putting them all together into a stock that comes out completely different, new, rich, and all our own.  I work at Guilford College, a historically Quaker institution and my colleague, Diya Abdo has begun an initiative, Every Campus a Refuge, to house refugees on college campuses, using student and faculty volunteers to help settle and work with the families. I have done a little work with ECAR, but after reading Alan Gratz’s book Refugee, I will definitely try to do more. There are many reasons kids (and their parents) should read Refugee. First of all there is the sheer pleasure of getting lost in a well-constructed page turner. Every chapter ends with a cliff hanger. The interwoven narratives increase the tension. Alan Gratz leaves readers on the edge of a precipice and then they have to speed through the next two chapters before finding out whether one of the three protagonists lives or dies. The cultural and historical details are interesting, authentic, educational, and introduced without clumsy information dumps. (My daughter is studying abroad in Cuba this semester and I was tickled to see how many details of Cuban life that she has relayed to us were included in the book). But the main reason kids should read Alan Gratz’s book is that refugee crises are a children’s issue. As the pictures in the news of children covered in dust or drowned on the beaches reveal, children are there, front and center. (Gratz mentions in the back matter that the image of Omram Daqneesh sitting in an ambulance inspired the character of Mahmoud's younger brother, Waleed.) These pictures display children as passive victims, but in Gratz’s book, the children have agency; they make choices; they take initiative. The child reader, identifying with them, is empowered and grows through their experiences. Take Josef, the boy from Nazi Germany, who flees to Cuba. With his father traumatized by the violence and inhumanity of a concentration camp, he must step up and become the man of the family. Isabel, the Cuban fleeing to America, trades her beloved trumpet for gas for their boat. Mahmoud, fleeing Syria for Germany, decides that it is more important to be visible than invisible and initiates a mass exodus from a detention center. In each narrative the roles of child and adult shift and transform as the children, jolted out of their ordinary lives, must perform feats of amazing bravery and strength. I am always interested in the backstory of books. Gratz tells in an interview how he and his family were on vacation in the Florida Keys and came upon a raft on the beach, a crude water craft clearly built of scrap materials to carry refugees from Cuba. The experience reminded him of his own privilege and ignited his curiosity. Drawing on the emotions and ideas provoked by this experience, he made boats and water a central motif in Refugee. Josef and his family sail on the unlucky MS St. Louis. The boat that Isabel travels in is cobbled together from fragments of this and that with an ironic poster of Castro on the bottom. Mahmoud makes a terrifying journey on a rubber dinghy across the Mediterranean in the dark. For all three families bodies of water, the space in between, provide escape and salvation, but also bring unmentionable terrors. In conclusion, the intertwined narratives make clear the perennial, ongoing nature of refugee crises. By profiling one family fleeing from Germany and another fleeing to Germany, one family fleeing from Cuba and another fleeing to Cuba, Gratz cleverly reveals how history repeats itself, but always with a twist. How does one become a refugee? Simply by being born in the wrong place at the wrong time. Gratz has said that he likes to remind children that unless they are Native Americans, someone in their family came here at some point as a refugee. Refugee teaches and encourages not just empathy, but activism. For my own part, I will now try to up my volunteer hours with ECAR.

I have found blogging discouraging. I write and post and then nobody responds. However, I recently received an intriguing message from the other side of the world (Australia) to one of my earliest posts. I had read a New York Times Op-Ed by Alberto Manguel about a secret library at Auschwitz. I was haunted by the idea of children in a concentration camp seeking comfort in books. Here is the blog I posted. It turns out I was not the only person haunted by Alberto Manguel's mention of a secret library at Auschwitz. In 2011 a Spanish journalist, Antonio Iturbe, read Manguel's book, The Library at Night, and using his considerable journalistic skills, he went in search of information. He found the actual librarian, the older girl, in charge of the eight threadbare books. Her name was Dita Kraus and she was then 80 years old and living in Israel. He wrote a novel in Spanish based on her story. The English translation, elegantly done by Lilit Thwaites, was just published to great acclaim this October by Henry Holt. Lilit's husband came across my blog post and contacted me. I promised to read and review The Librarian of Auschwitz, which I stayed up finishing last night, with a box of kleenex at my side. The Librarian of Auschwitz is the perfect follow up to Anne Frank for the young adult and adult reader. It details the horrors of the camps, the inhumanity of genocide, and the amazing spirit and light of those individuals whose names and stories we must never forget. Here in the US, where fascists chanting "blood and soil" march with tiki torches through the lovely town of Charlottesville, we especially need to be reminded. But, The Librarian of Auschwitz is not just about the holocaust. It is also a story about the magic of books. Iturbe describes eloquently the power of books to transport readers to other places and times. What could be more important than to escape metaphorically for an hour from the horrors of a concentration camp? As Iturbe explains, for Dita this magical power inhered not just in novels, but even in H. G. Wells's A Short History of the World: A Short History of the World is the library book borrowed most frequently because it's the closest thing to a regular schoolbook. And there's no question that when she buries herself in its pages, she feels as if she were back at her school in Prague, and that if she were to raise her head, she'd see in front of her the blackboard and her teacher's hands covered in chalk. (114) Here Wells' book returns her to the comfort of her life before it was interrupted by war. But it also carries her far, far away. That's why she prefers to return to the pages about ancient Egypt, which immerse her in the world of pharoahs with mysterious names and allow her to board the boats that navigate the Nile. H. G. Wells is right. There really is a time machine--books". (116) Dita is in charge of not just books on paper, but also living books, the stories narrated by gifted tellers. One of the most moving scenes in the novel is when a fellow inmate tells Dita the story of The Count of Monte Cristo. She is drawn to the figure of Edmond Dantes. She also wonders if, were she successful [in escaping], she'd dedicate her life to taking revenge on all the SS guards and officers, and if she'd do it in the same methodical, implacable, and yes, even merciless, manner as the Count of Monte Cristo. Of course she'd be delighted if they suffered the same pain they inflicted on so many innocent people. But nevertheless, she can't avoid feeling some sadness at the thought that she liked the happy and confident Edmond Dantes of the beginning of the story more than the calculating, hate-filled man he became. (278) Here books give her a way to explore the ethics of revenge and to sort through the immensely complicated emotions of her experience.

It was through the magic of books, specifically Alberto Manguel's book, The Library at Night, that Iturbe came across Dita's story. I am thankful to him. I am thankful to Iturbe for writing the novel that has brought the story to life, and I am thankful to Lilit Thwaites for making the novel available to English speaking audiences. I am thankful to Lilit's husband to reaching out to me. Books have ripple effects. One cannot anticipate how and where these ripples will expand. It is my hope that the waves from The Librarian of Auschwitz will reach far and wide for a long time to come. First I want to thank Eliza Wheeler's amazing husband who had the computer skills to put together this trailer for John Ronald's Dragons. The way he makes the figures in the background move is called parallaxing. As someone who struggles daily with simple classroom management software (moodle an canvas ugh!) I am forever impressed by and grateful to those who can combine technical and creative skills with grace. Second, I want to point out that last Saturday, March 25th, was Tolkien reading day. Our Carolinas SCBWI leader, Teresa Fannin, sent me a beautiful article explaining the significance of the date. Apparently dates in Tolkien's books are just as carefully chosen as the names of his characters. I celebrated Tolkien reading day by reading John Ronald's Dragons at Scuppernong's Bookstore, a warm, quirky community bookstore in downtown Greensboro. Third, I want to review a book I read over my spring break, Adam Gidwitz's middle grade novel The InQuisitor's Tale.  The Inquisitor's Tale by Adam Gidwitz is amazing! This is the book I wish I had written. It is the book I wish I could go back and read to my kids using my special time turner travel kit. It is the book I wish the college kids I teach had grown up reading because it would make them wise, thoughtful, and literate about that strange country, the past, more specifically the past of the middle ages. Adam Gidwitz's three main characters are two boys and a girl as in the Harry Potter formula, but he builds on this formula by adding a dog and by making one child black, one child Jewish, and one child a peasant, thus taking on the topics of class, race, and religion. Gidwitz builds on actual Saints' legends, which are great and gory stories, and mixes them up with the modern superhero trope. And what are saints but superheros with magical powers? The mash up makes the past new and the present old. Again following a classic kid lit formula the three children are relieved of parental comfort and authority early in the novel. In picaresque fashion they wander the French countryside and have adventures with silly knights, a farting dragon, a close minded queen, and a fat angel. But along with the fart jokes, Gidwitdz takes on deep questions: the origins of mistrust and conflict between Christians and Jews, the construction of racial difference, the banning and burning of books and the biggest question--if God is good, why does he allow terrible suffering. Also, the book is beautiful to behold. The illustrator, Hatem Aly, has decorated the margins with charming illuminations and doodles that are like the text, historically informed but also modern. I now want to read the book a second time (I had to read it really fast the first time to find out what happens), and dawdle and peruse the pictures and their relationship to the text. I also love that this is a book about mutual understanding between different religions and the author is Jewish and the illustrator is Muslim. What could be more perfect? And for adults who read the book to their children (and why wouldn't you?) you must read the elegant author's note which explains how much of the story is based on actual medieval legends and lore. John Ronald's Dragons has launched, and it is thrilling to hear from all of the people who are reading and enjoying it. As the book has come out so have the reviews. Publishers Weekly really understood the purpose of the book, to introduce younger readers to Tolkien before they encounter him in middle or high school. Here is their review:

The dragons of imagination are always there, but sometimes it takes time for them to breathe fire—that’s what McAlister (Holy Molé!) suggests in this thoughtful look at the creative development of John Ronald, aka J.R.R. Tolkien. Reflecting Ronald’s lifelong preoccupation with dragons, Wheeler’s (This Is Our Baby, Born Today) illustrations blend hints of the fantastical and the mundane—chimney plumes and steam from a young Ronald’s oatmeal mimic the smoke curling from an imagined dragon’s nostrils. McAlister moves briskly through Ronald’s life, touching on the influences of his faith, military service, and education before he hit upon the invention of a hobbit, one who would lead him all the way to “a dragon named Smaug.” It’s an ideal lead-in to family readings of The Hobbit. Ages 4–8. Author’s agent: Jennifer Mattson, Andrea Brown Literary. Illustrator’s agent: Jennifer Rofé, Andrea Brown Literary. (Mar.) The Horn Book also gave the book a good review and points out how I introduce Tolkien's themes and show their origins in his childhood. This picture-book biography of J. R. R. Tolkien shows the roots of many themes later found in The Hobbit and the Lord of the Rings trilogy. McAlister introduces John as a boy who loves horses, trees, words, and especially dragons. We see young John encountering dragons in Andrew Lang’s famous colored Fairy Books, making up a language with his cousin, and eventually fighting in WWI, teaching, and writing stories. Despite Tolkien’s sometimes-difficult young life (after his mother died, he and his brother lived with an aunt who “didn’t like boys”), the prevailing tone is one of warmth and security. Wheeler’s illustrations, in what look like line and watercolor, are deftly executed in light colors with carefully placed darker shades that ground her compositions. Swirling shapes and trees silhouetted against pearly skies are reminiscent of Rackham, an appropriate reference given the subject and time period. The book finishes with Tolkien’s conception of The Hobbit; the final illustration shows the author “discovering” the great dragon Smaug in his mountain cave. An author’s note fills in the gaps in Tolkien’s story, and an illustrator’s note points out pictorial references to actual books, locations, and people not mentioned in the text. “A Catalog of Tolkien’s Dragons,” “Quotes from Tolkien’s Scholarly Writing on Dragons,” and a bibliography are appended. lolly robinson The one not so nice review came from School Library Journal, a big disappointment since I want to sell to schools and libraries: Gr 1-4–McAlister’s picture book introduction to the life of J.R.R. Tolkien (whom she calls John Ronald) is written in simple, descriptive language—a fragment to six short sentences per page or spread. (“John Ronald was a boy who loved horses. And trees. And strange sounding words.”) Critical to John Ronald’s life were the “stillness, beauty, and peace” of the Catholic Church; his love of English (coming up with new languages and using them to write stories); his lifelong school friends who shared his love of literature; and his dreams of dragons and other fantastical creatures that inhabited the books read to him and his brother by their mother, who died when John Ronald was 12. After marrying, then fighting in the trenches during World War I, Tolkien taught at Oxford University, where he gave lectures, went to meetings, tutored students, and “graded many, many, exams.” The world of the Hobbit and his adventures, created for Tolkien’s own children, became a book in 1937. Wheeler’s pencil-detailed paintings in subdued greens and yellows effectively portray Tolkien’s quiet life and his ability to imagine magical creatures and places (Misty Mountains, Mirkwood Forest) in the countryside around his home. The appended illustrator’s note points out elements in the pictures not mentioned in the text. An author’s note offers more sophisticated facts; a bibliography lists Tolkien biographies for adults. VERDICT This beautifully illustrated introduction to Tolkien’s life for younger readers fails to provide sufficient information to satisfy those old enough to appreciate the lengthy, in-depth storytelling style of his novels.–Susan Scheps, formerly at Shaker Public Library, OH This last reviewer wanted a different kind of book, a middle grade or YA biography because Tolkien's books are read by middle grade and YA readers. But my conception and Eliza's as well was to write a book about how a writer's imagination begins to take shape in childhood and to write this for children. What I have learned as a teacher from this experience is to be a more thoughtful grader, to think not about the ideal paper I have in my head, but to think about the student's objectives, the student's purpose in creating a piece of writing and whether the student has achieved that purpose. The next set of papers I get, I will ask students to articulate for me what they have tried to realize with this piece of writing. (Just doing that is an important step as a writer.) Then I will try to grade them based on whether their creation does what they meant it to do. . |

Caroline McAlisterCaroline is an avid reader, children's writer, and teacher. She lives in North Carolina with her husband and dog. Check out her bio for more! Archives

February 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed