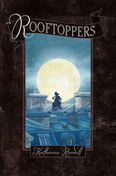

,So I've been trying to expand my repertoire beyond the picture book biography, and to that end, I have been reading a lot of middle grade novels. My favorite at the moment is Rooftoppers by Katherine Rundell. I found out about her because she had reviewed The British Library's Harry Potter exhibition for the London Review of Books. www.lrb.co.uk/v39/n24/katherine-rundell/at-the-british-library. She grew up on Rowling's books and shares with her a genius for the tropes of classic British children's fiction: quasi-fantastical Victorian settings, orphans, and eccentric guardians. The gangs of enterprising street children are reminiscent of Charles Dickens and Eric Kastner.  Apparently Rundell was inspired to write Rooftoppers by her own adventures climbing the roofs of Oxford. (It is no accident that Philip Pullman blurbs her book.) Here is a link to an article she wrote about climbing for the London Review of Books. www.lrb.co.uk/v37/n08/katherine-rundell/diary I am interested, however, in what I can learn as an aspiring middle grade writer from Rundell. I feel my weakness is plot so I am intrigued by how other authors construct theirs. The plot of Rooftoppers is driven by the main character's, Sophie's, desire for her lost mother. Although Sophie is still an infant when she is separated from her mother, she has memories: "Sophie's skin was too pale, and it showed blotches in the cold, and her hair had never, in her memory, been without knots. Sophie did not mind, though, because in her memory of her mother she saw the same sort of hair and skin--and her mother, she felt sure, was beautiful. Her mother, she was sure, had smelled of cool air and soot, and had worn trousers with patches at the ankle" (13). I love the detail of the patches at the ankle because a small child would notice things at ankle height. But to get back to plot, everything depends on these memories of love and connection. Sophie clings fiercely and stubbornly to them, coming to think of herself as a "mother-hunter." So lesson number one is the plot must be driven by the main character's desire. In children's fiction the desire for a parent's love is powerful. Lesson number two has to do with the obstacles Rundell creates for Sophie to overcome before she can realize her desires. She faces external obstacles: a conformist child services bureaucrat, unhelpful French authorities (imagine!), and a feral gang of French street children. But she also faces internal obstacles: her fear of the water and her fear of heights. The internal and external obstacles are inextricable. She cannot overcome one without overcoming the other. So lesson number two is throw exciting challenges in front of your character that create tension, but also allow the character to grow internally and mature. Lesson number three has to do with Rundell's similes. I love the way she uses similes to describe feelings, especially feelings of joy and wonder connected to music and reading. For example, she describes how Sophie's eccentric guardian sings with perfect pitch: "Charles had no musical instruments, but he sang to her, and when Sophie was elsewhere, he sang to the birds, and to the wood lice that occasionally invaded the kitchen. His voice was pitch-perfect. It sounded like flying" (10). Then there is the first time that Sophie hears cello music: "It was so beautiful that it was difficult for her to breathe. If music can shine, Sophie thought, this music shone. It was like all the voices in all the choirs in the city rolled into a single melody. Her chest felt oddly swollen" (24). And most wonderful of all is the description of a good cello practice session. "When the music went right, it drained all the itch and fret from the world and left it glowing. When she did stretch and blink and lay her bow down hours later, Sophie would feel tougher, and braver. It was, she thought, like having eaten a meal of cream and moonlight" (26). A meal of cream and moonlight! I love that she uses synaesthesia, comparing the sound of music to the taste of food. I once went to a talk by Itzhak Pearlman and he described Beethoven as sounding like beef. Lesson number three: the writer's job is to make the reader experience what she describes, and synaesthetic similes can do that. I will obey the rule of three and stop here. If you read this post, please let me know what middle grade novels you have enjoyed and what writing tips you have gleaned from them. P. S. Here is one more link to an article about Rundell's newest book, The Explorer, which I may just have to read next.

64 Comments

|

Caroline McAlisterCaroline is an avid reader, children's writer, and teacher. She lives in North Carolina with her husband and dog. Check out her bio for more! Archives

February 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed